No, we are not underinvested in squishy charities

09 Dec 2024This weekend the New York Times published an essay by Emma Goldberg titled, What if Charity Shouldn’t Be Optimized?. It argued that effective altruism (EA) – which uses cost/benefit analysis to fund easily quantified causes like malaria prevention and lead abatement – might detract from “squishier” causes like museums and community groups.

In the comments, Goldberg praised readers who choose to donate to American universities, libraries, and local animal shelters instead of EA causes. One commenter, contrasting themselves with EA, wrote “I give to organizations it feels good to give to” and another said they donate “based on my heart, not metrics”. Goldberg responded positively to both.

The essay stresses that there is nothing wrong with trying to optimize charitable giving. But it expresses concern that too much “hyper-rational” giving may shift focus away from local charities that foster community or are harder to measure.

Goldberg is right that there is value in hard-to-quantify causes, and that charitable giving should reflect a diversity of priorities, including community-based initiatives. Most people would agree with her, including leaders of the EA movement.

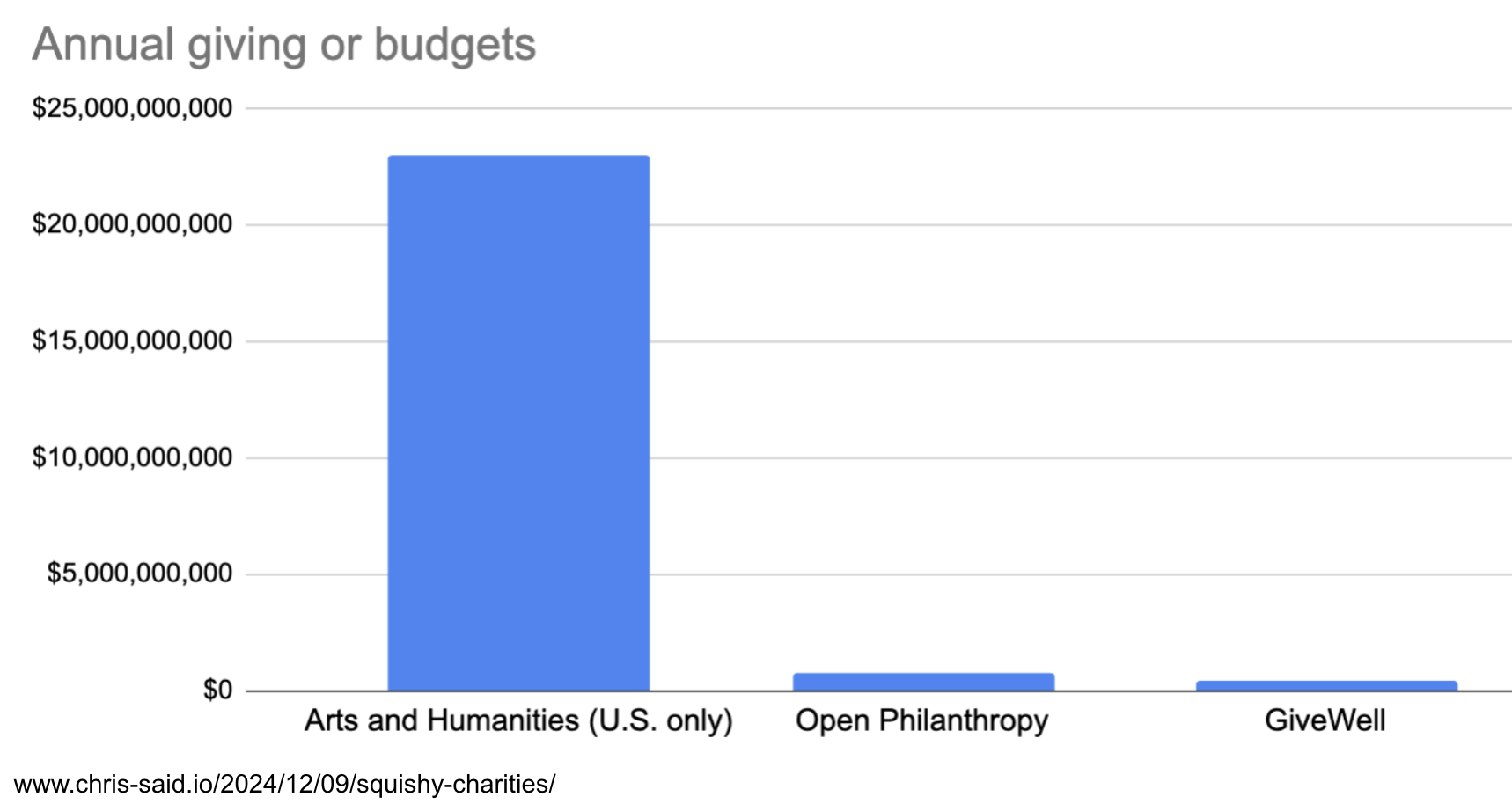

But the idea that the global charity budget has shifted too far toward EA is preposterous. Consider the following:

- Americans give $23 billion to the arts and humanities every year. That’s 30 times the $750 million budget for Open Philanthropy and 60 times the $400 million budget for GiveWell, the two most prominent EA foundations.

-

While only 0.007% of U.S. animals killed are in companion animal shelters, 95% of animal charity donations go to this cause. Meanwhile, just 3% of animal charity donations, all EA-related, go to the much larger problem of factory farming. (Source)

-

Americans gave $557 billion to charities in 2023. If we generously assume $15 billion were to EA causes (i.e including $8 billion from the EA-adjacent Gates Foundation), that accounts for just 2.5% of total U.S. giving.

-

I can find no evidence that donation dollars to squishier causes has decreased, and none was presented in Goldberg’s essay.

So contra Goldberg’s essay, these numbers show we are overindexed on squishier causes, particularly when you consider how much EA has done with its limited resources. GiveWell alone has saved the lives of 200,000 human beings, and EA-aligned animal welfare orgs have convinced farmers to move 400 million chickens out of cages.

Defenders of the squishier charities might say their causes should not be quantified. But when they donate $1 million to restore a painting, while GiveWell estimates they could save a life for $3,000, they are implicitly valuing the painting’s restoration at more than 333 human lives. That’s not my quantification. That’s their quantification, based on their own choices!

A balanced charitable portfolio that includes both community organizations and global health initiatives is worth striving for, even if some of the causes are hard to quantify. But the balance Goldberg is encouraging is indefensible.

The world doesn’t need less optimization in charitable giving; it needs more awareness of the extraordinary good that can be done when we take the time to quantify impact.

Special thanks to Alexander Berger for his tweet thread inspiring this post.