Double descent in human learning

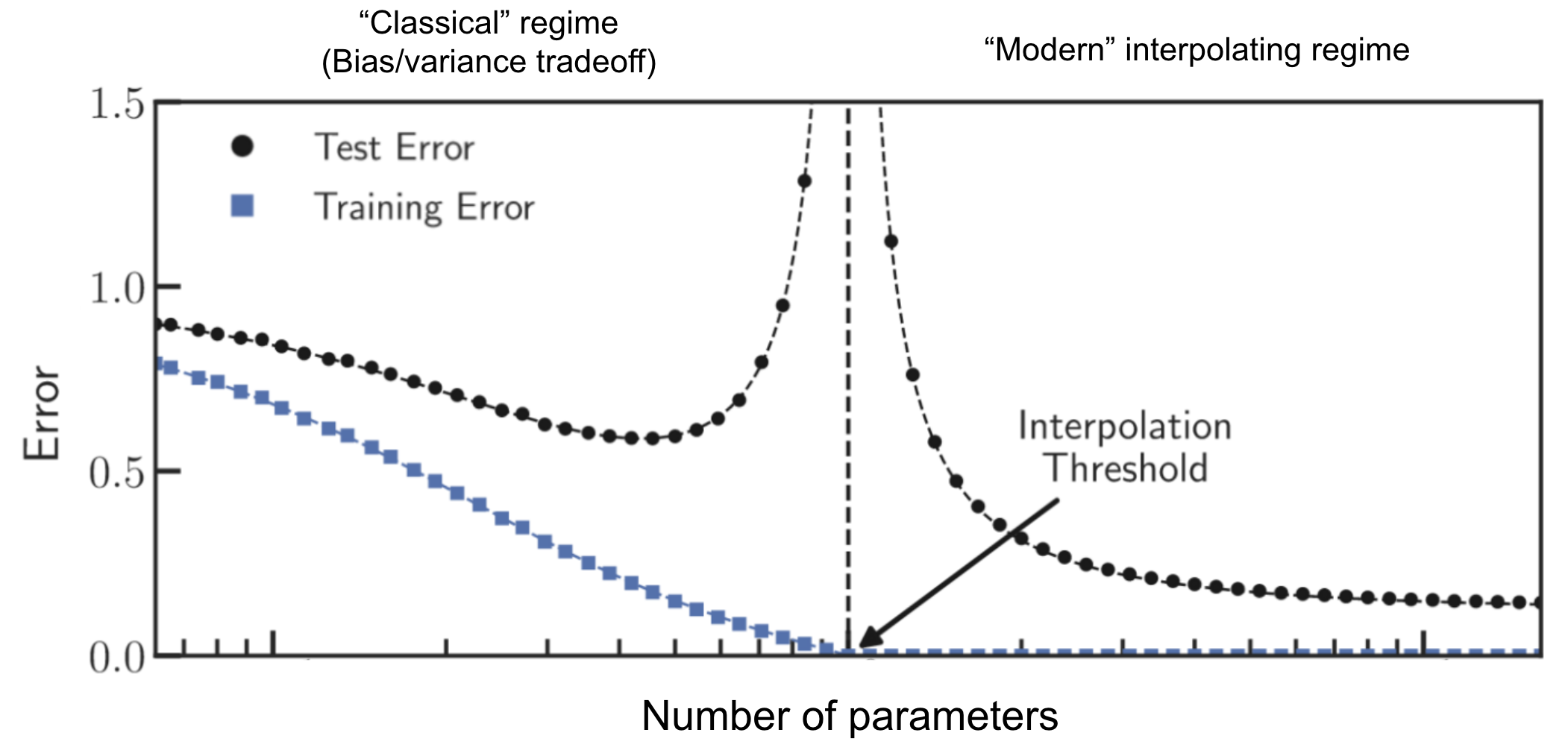

21 Apr 2023In machine learning, double descent is a surprising phenomenon where increasing the number of model parameters causes test performance to get better, then worse, and then better again. It refutes the classical overfitting finding that if you have too many parameters in your model, your test error will always keep getting worse with more parameters. For a surprisingly wide range of models and datasets, you can just keep on adding more parameters after you’ve gotten over the hump, and performance will start getting better again.

Figure 1. Parameter double descent in machine learning. As more parameters are added to a model, test error decreases, then increases, and then decreases again. Figure adapted from Rocks et al. (2022)

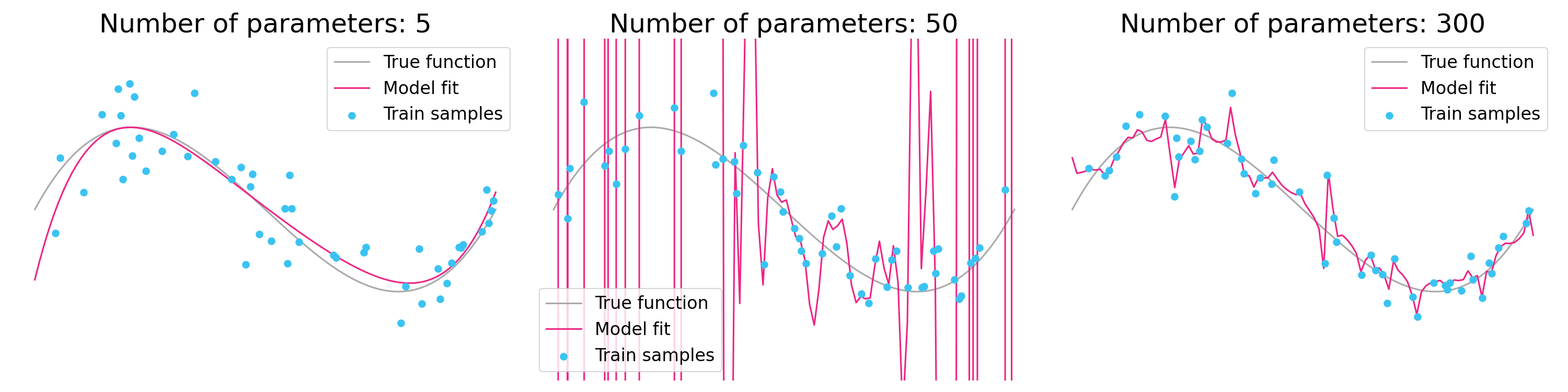

The surprising success of over-parameterized models is why large neural nets like GPT-4 do so well. You can even see double descent in some cases of ordinary regression, as in the example below:

Figure 2. Parameter double descent in linear regression with Legendre polynomial basis functions. Performance is best with a small or large number of parameters, but worst for an intermediate number of parameters. [Notebook]

Similar to classical overfitting, double descent happens both as a function of the number of model parameters and as a function of how long you train the model. As you continue to train a model, it can get worse before it gets better.

This raises an interesting question. If an artificial neural network can get worse before it gets better, what about humans? To find out, we’ll need to look back at psychology research from 50 years ago, when the phenomenon of “U-shaped learning” was all the rage.

This blog post describes two examples of U-shaped learning, drawn primarily from the 1982 book U-Shaped Behavior Growth.

Language learning and overregularization

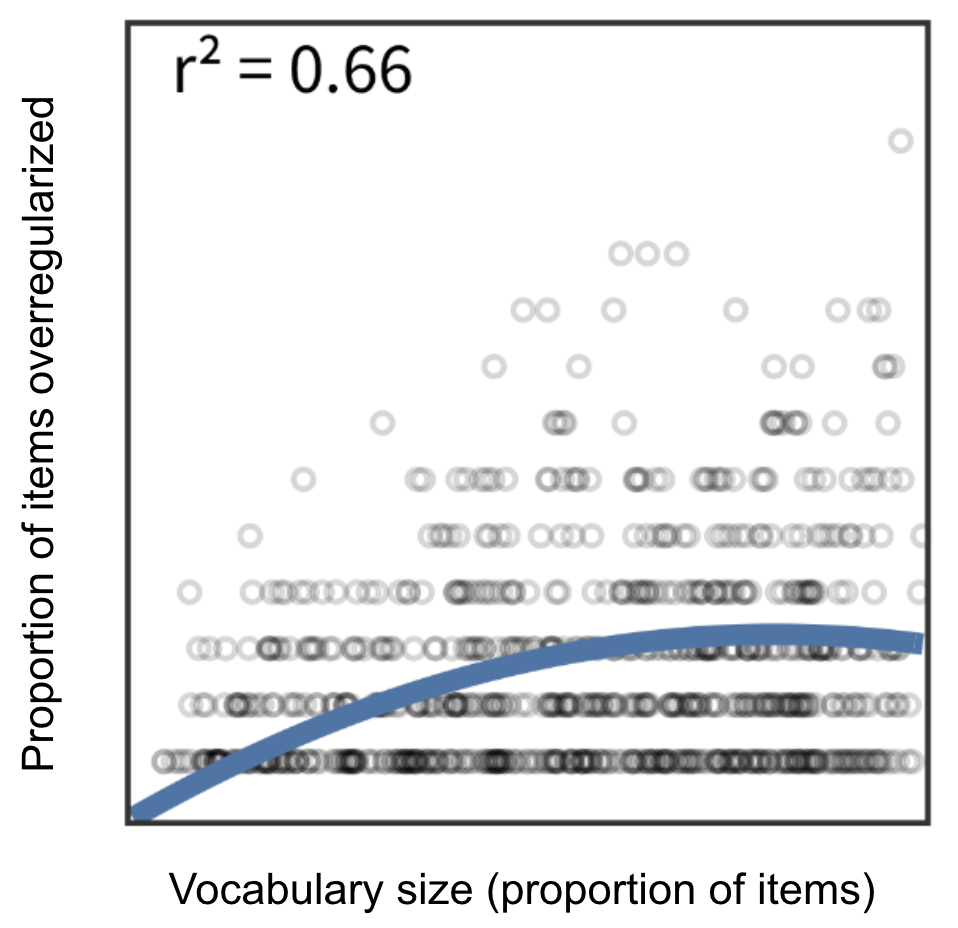

When kids are learning to talk they can often use the correct form of regular nouns and verbs (“shoes”, “dogs”, “walked”, “jumped”) as well as irregular nouns and verbs (“feet”, “mice”, “went”, “broke”). But at a second stage of development, they start to overgeneralize certain grammatical rules to words that should remain irregular. For example, “feet” becomes “foots”, “mice” becomes “mouses”, “went” becomes “goed”, and “broke” becomes “breaked”. Only at a third stage of development do the correct words reemerge.

Figure 3. Proportion of nouns over-regularized in American English, as a function of children’s vocabulary size, which grows with age. As children get even older (not shown), the proportion will drop down to about zero. Figure adapted from Frank et al. (2021). Additional statistical tests on separate data sets can be found on p.40 of a 1992 book chapter by Gary Marcus.

Why does this happen? The initial correct usage comes from learning individual cases, in isolation from each other. After having acquired some examples of a regular pattern, the child learns abstract rules like “-ed” for past tense or “-s” for pluralization. These are then over-generalized to irregular words. Only later does the child learn when to apply the rules, and when not to.

Understanding physical properties like sweetness and temperature

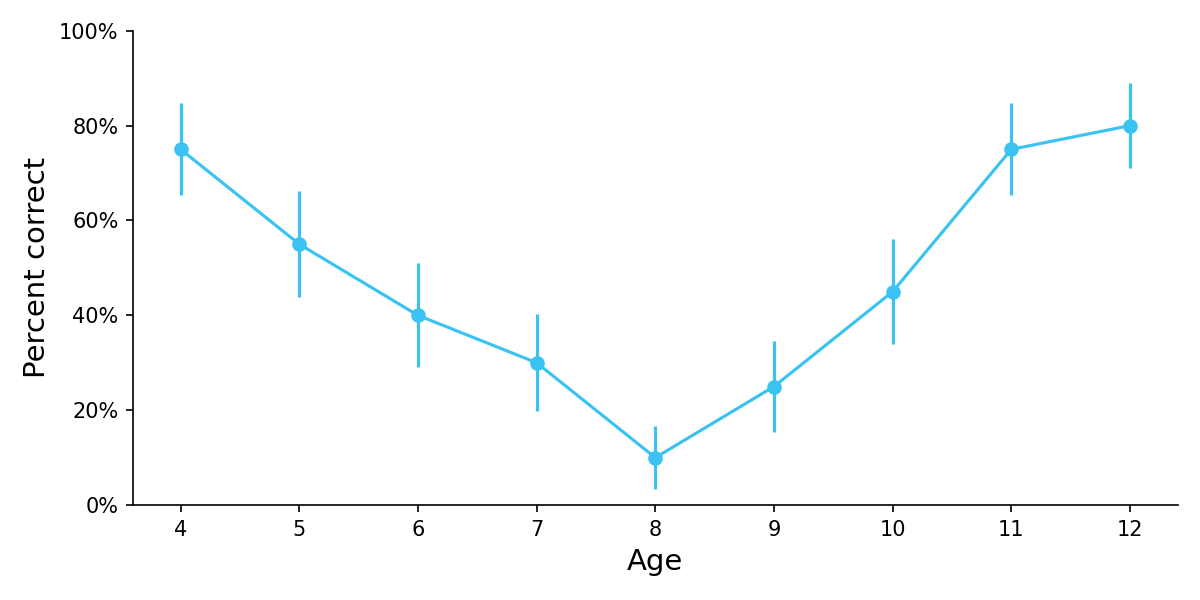

Children display a U-shaped learning curve in understanding physical properties such as sweetness, with children at an intermediate age believing that if you mix together two glasses of equally sweetened water, the resulting solution will be even sweeter than the original (Stavy et al., 1982).

Figure 4. Percent correct on a task requiring children to guess the sweetness of water produced by combining two equally sweetened glasses of water. Error bars show SEMs. Adapted from Table 1.1 of Stavy et al. (1982) in Chapter 2 of U-Shaped Behavior Growth.

A similar result was found with water temperature (Strauss, 1981).

The regression occurs because children try to generalize a newly-learned principle (additivity) to a domain where it shouldn’t apply (concentration of a solution or temperature).

Other examples of U-shaped learning

U-shaped learning has also been reported in a social cognition task (Emmerich, 1982), a motor coordination task (Hay et al., 1991 and Bard et al., 1990), and a gesture recognition memory task (Namy et al, 2004). For those who want to learn more about the history of U-shaped learning, this 1979 New York Times article is really interesting. They sent a reporter to a U-shaped learning conference in Tel Aviv!

Does U-shaped human learning teach us anything about double descent?

U-shaped learning curves are an interesting curiosity with clear relevance to psychology. But do they teach us anything about double descent in artificial neural networks?

Maybe! While some of the examples bear only a superficial relationship to double descent, there is a stronger relationship with the language learning example (“went”→”goed”, “mice”→”mouses”), although not in the way double descent is normally presented.

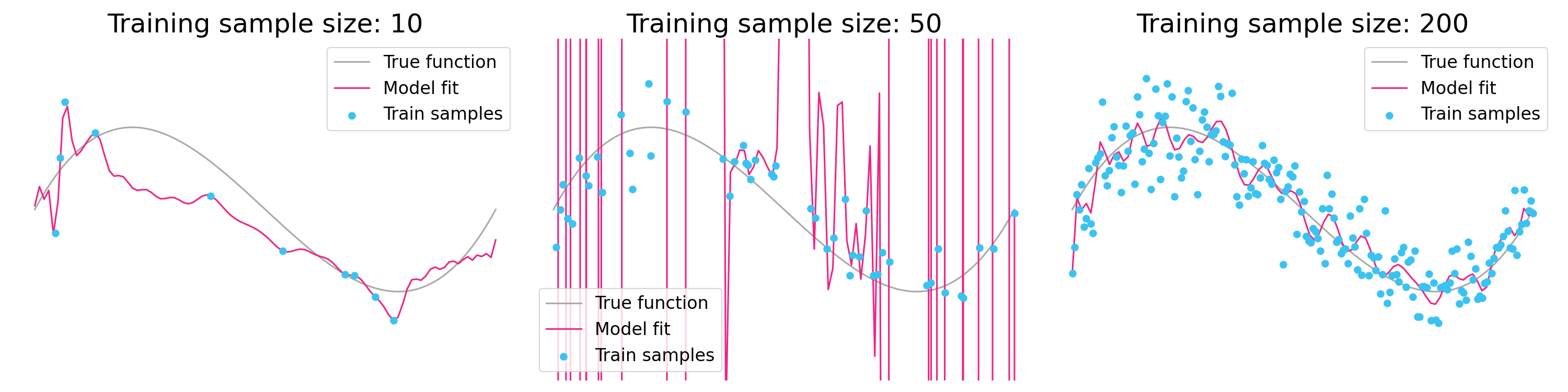

The way double descent is normally presented, increasing the number of model parameters can make performance worse before it gets better. But there is another even more shocking phenomenon called data double descent, where increasing the number of training samples can cause performance to get worse before it gets better. These two phenomena are essentially mirror images of each other. That’s because the explosion in test error depends on the ratio of parameters to training samples. As you increase the number of parameters (double descent), the explosion occurs when transitioning from an underparameterized regime (p<n) to an overparameterized regime (p>n). As you increase the training sample size (data double descent), the explosion occurs when transitioning from an overparameterized regime (p>n) to an underparameterized regime (p<n).

Figure 5. Data double descent. In contrast to Figure 2, the three plots all share the same number of parameters but vary in the number of training samples. As more samples are added, performance gets worse before it gets better. Note that the high number of parameters is inappropriate for a simple regression problem, but would be quite common in a neural network setting. [Notebook]

In some ways, the language learning example is a reasonable analogue of data double descent. Children start off in an overparameterized regime where they have essentially memorized the small amount of training data. Eventually they get enough data that they can learn some rules, which they unfortunately overgeneralize to irregular examples, similar to high test error in a machine learning setting. Only when they have been exposed to a large amount of data are they able to build a more flexible and correct set of rules.

I’m not ready to say that U-shape learning in human brains is identical to double descent in machine learning. Performance degradations in U-shaped human learning are typically confined to local subsets of tasks rather than global performance, and these local degradations can emerge in deep networks even without the exploding parameters observed in ML-based double descent (Saxe et al., 2019). But U-shape learning is still a great example of how switching between different regimes can cause performance degradations, whether in artificial neural networks or in the largest neural net in the known universe.

Appendix: A direct explanation of double descent

It’s easiest to understand double descent in the linear regression case. When a model is just barely able to fit the training data perfectly, it’s likely to pick a bad set of coefficients that don’t generalize well, at least under a set of fairly common conditions that Schaeffer et al. (2023) outlines. But as even more parameters are added in the overparameterized regime, the model can consider multiple different ways of perfectly fitting the training data. At this point it has the luxury of picking the set of coefficients with minimum norm, achieving better generalization via regularization.

Surprisingly to me, this sort of regularization happens naturally even without explicit regularization. That’s because two common solutions to linear regression (gradient descent and minimum norm least squares) will both implicitly find the best fit with minimum norm. And since deep learning finds its parameters with an optimization method similar to gradient descent, it too can experience double descent.

For more on this, the clearest and most accessible explanations are in Schaeffer et al. (2023) and in this thread by Daniela Witten.