The uncertainty pill

17 Apr 2022Think of a view you hold politically. Bear with me, and ask yourself a few questions. How well do you really understand the issue? Have you thought through all of the second and third order consequences? Did you consider perverse incentives? What will happen when your plan is played out for multiple generations? Did you apply a discount factor? Do you know what the discount factor should be? Are there risks to your plan that you haven’t thought of? How well can you articulate the beliefs of your opponents? Do you know why your opponents are so certain? Is there any chance those reasons could apply to you?

With only a few exceptions that I’ll address later, I think it’s weird to have strong political views. The world is a complex system, and complex systems are notoriously hard to reason about. Unintended consequences abound. And yet wherever I look, people fight about complex topics they don’t understand, certain that the other side is wrong or evil. Sometimes these fights tear families apart. It’s bad.

I don’t have many strong opinions. I’ve been uncertainty-pilled, and I’d like to tell you about it.

What is the uncertainty pill?

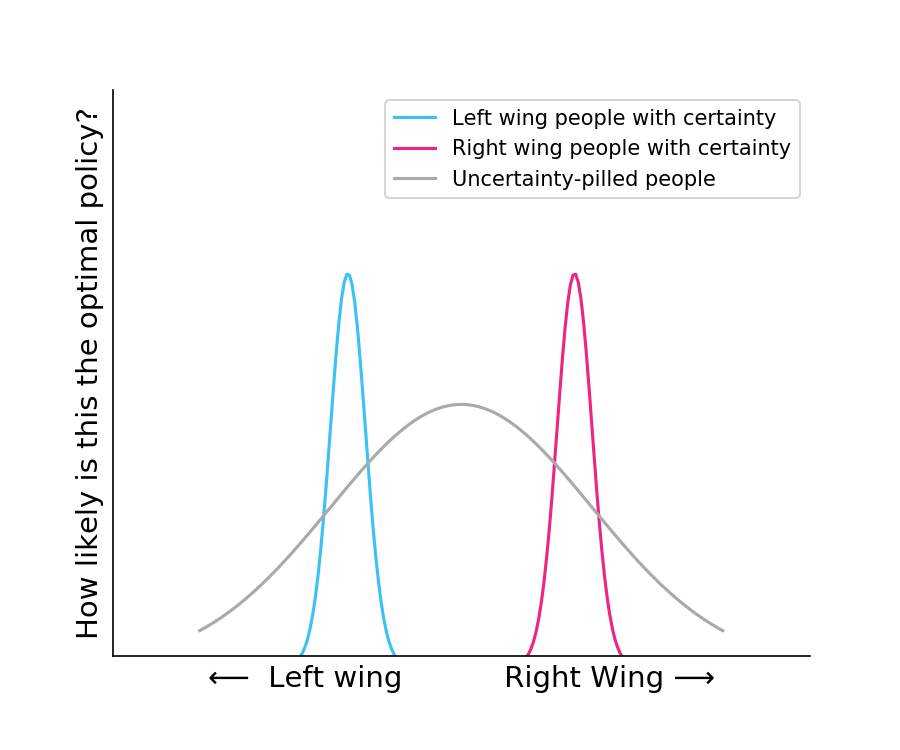

People who have taken the uncertainty pill think the future is extremely hard to predict, making it difficult to know the optimal policy. Consider the US political spectrum, as shown in the diagram below. Most on the Left (blue) or Right (pink) are certain that they are correct and their opponents are wrong. The uncertainty pill (gray) says that either of them may be correct and that both might be wrong.

The uncertainty pill is not centrism

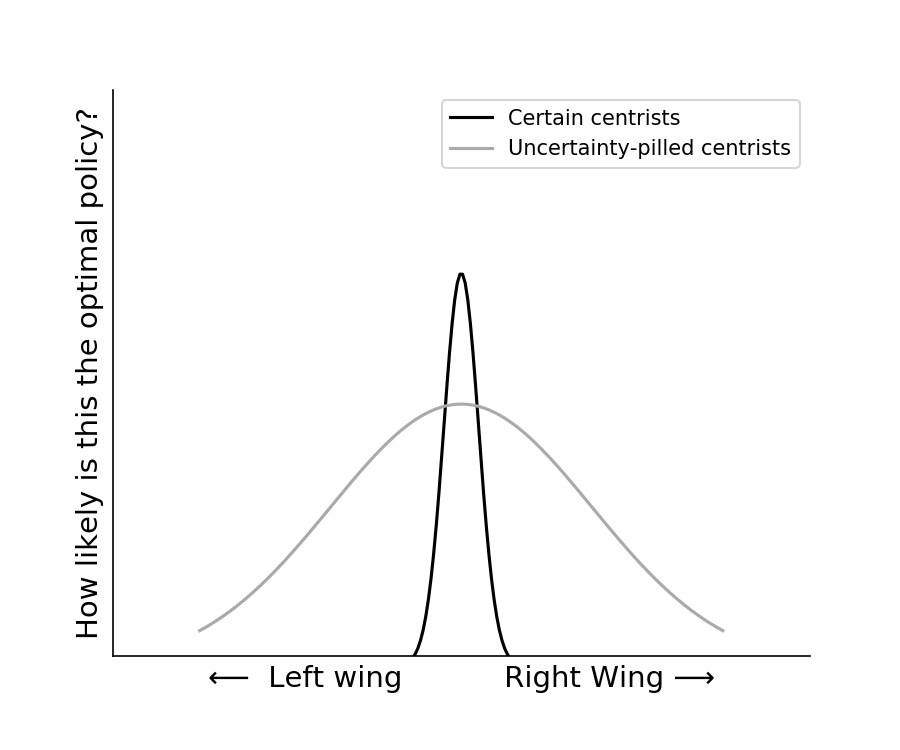

The uncertainty pill is related to centrism, but is not the same. In the diagram below, a conventional centrist is certain that centrist policies are the correct policy (dark gray). An uncertainty-pilled centrist is not (light gray). To them, the centrist policy may be most likely to be correct, but there is still a decent chance that a Leftist policy or a Rightist policy is correct.

Uncertainy-pilled people can still pick sides

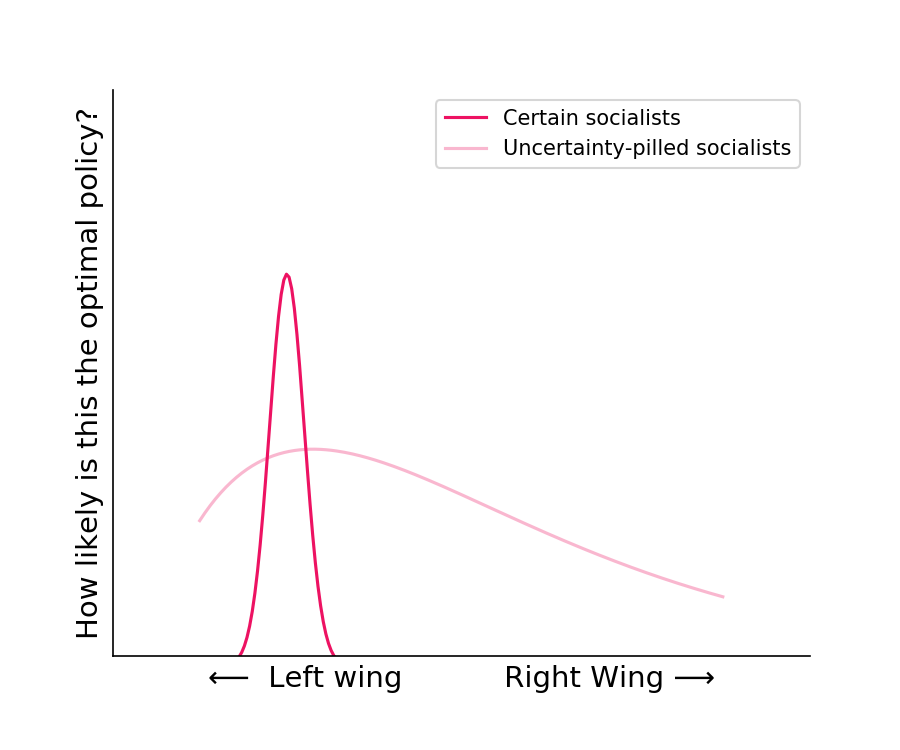

The uncertainty pill does not prevent you from picking sides. It is possible, for example, to be an uncertainty-pilled socialist. A conventional socialist is certain about their beliefs, thinks the other side is morally bankrupt, and cannot clearly articulate opposing points of view. An uncertainty-pilled socialist may prefer socialism, but recognizes a real likelihood that other views may be correct.

The uncertainty pill is chill

High certainty people tend to be quick to judgment and quick to anger. Uncertainty-pilled people think that most other people have good intentions. They have the scout mindset, not the soldier mindset. The uncertainty pill makes you chill.

So the next time you see people fighting about something they don’t really understand, take a bite of the uncertainty pill and relax. Maybe offer a few thoughts, but remember that the world is complex and none of us understand it as well as we think we do.

Caveat time

As an uncertainty-pilled person I love caveats, so let me close with one.

While the uncertainty pill looks down on people who are overly certain, it is sympathetic to some forms of certainty. In particular, it’s reasonable for marginalized or oppressed people to fight for their own interests. Since those people are focused primarily on their own well-being – which they are experts in – they may correctly have some certainty about the impact on themselves. For example, a low-wage worker fighting for better working conditions at their company is probably fighting for an outcome truly in their own best interest.

But if you are privileged, you can afford to advocate for issues beyond your narrow self interest. If you do that, you’ll need to make claims about broader society and broad time horizons – precisely the claims where certainty is no longer justified. It is your responsibility to be thoughtful, open-minded, and uncertain. The answers are not simple. And if you think they are, you haven’t thought about them enough!

Related ideas: Consequentialist cluelessness

Special thanks to John McDonnell for discussions