Pandemic virus prediction: All risk and minimal benefit

18 Dec 2021At this moment, a growing number of scientists are studying viruses that have not yet infected human populations, seeking to understand and publish information about how deadly they are. Some of these viruses are found in animal populations. Others are partially engineered by scientists, often specifically to make them more deadly or more transmissible. Scientists who conduct this type of research, which has been called pandemic virus prediction, say it could help us get ahead of the next pandemic. Critics say it’s risky.

The risks are far higher than you think, and the benefits far lower than you think. Much of this post is based on congressional testimony and an extraordinary interview on Julia Galef’s podcast with MIT biosecurity researcher Kevin Esvelt.

The risks: It’s not the lab leaks, it’s the mail-order DNA

Much of the debate about pandemic virus prediction centers around lab leaks. Lab leaks are common, and many biosecurity experts believe that risk alone outweighs the benefits.

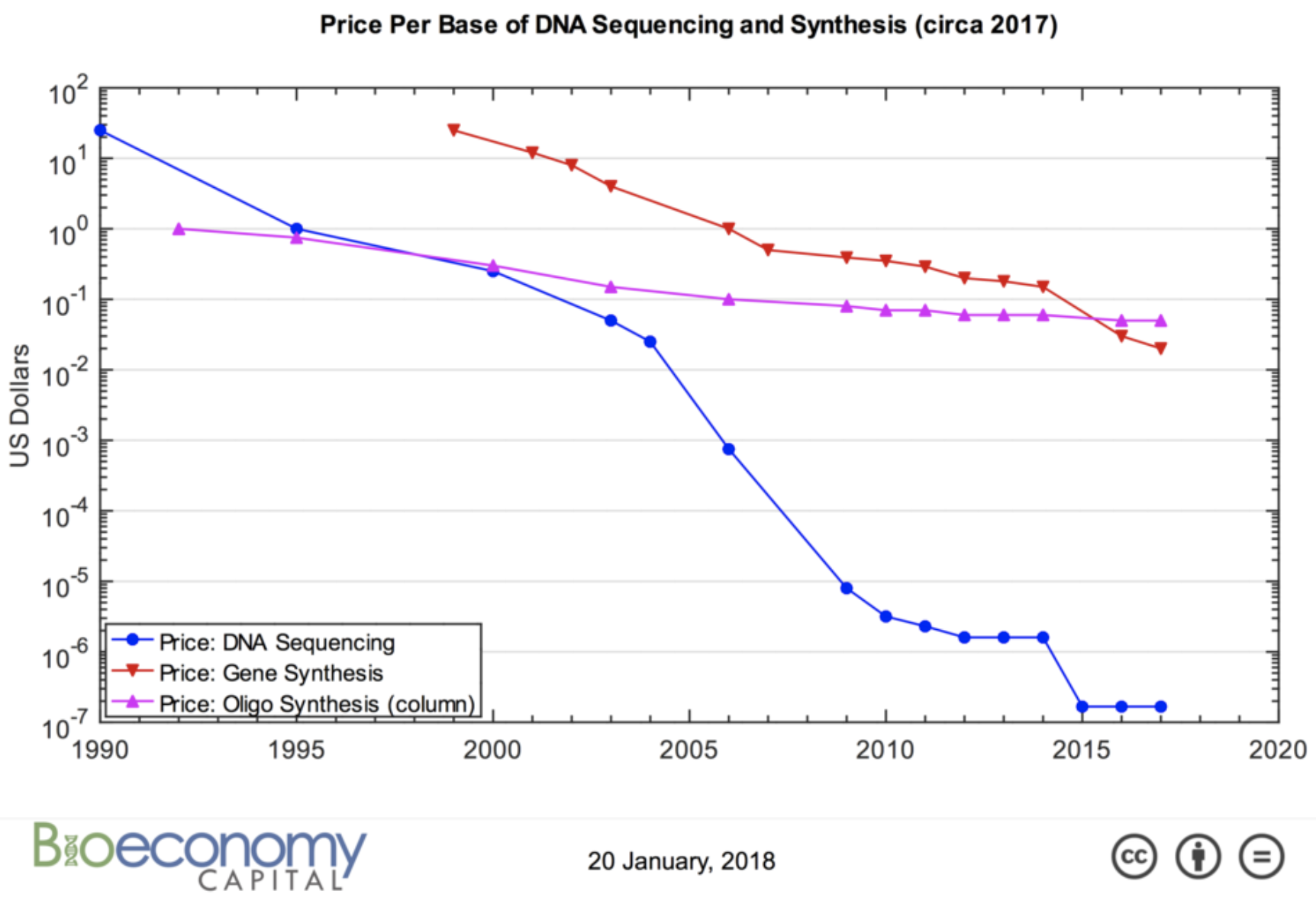

But do you know what’s scarier than lab leaks? Exponentially decreasing costs of mail-order DNA and virus assembly. At this moment, thousands of individuals are capable of assembling a pandemic-capable virus, once we identify one. As the cost of synthetic DNA and virus assembly continues to decline, even more people will be able to do this.

Figure 1. Price per base of DNA sequencing and synthesis, log scale (Source: Bioeconomy Capital).

The risk here is unfathomable. Unlike nuclear warfare, which had the comforting stability of large rational actors, bioterrorism can be untraceable and asymmetric. It just takes one crazy person to create a pandemic. All they have to do is look up the published sequence to a deadly pandemic virus, order the nucleic acids in the mail, and assemble a virus using known protocols.

The benefits

Researchers who conduct pandemic virus prediction say it will help us “get ahead” of the next pandemic. But upon deeper inspection, these claims are rather weak.

The first claim is that if we can identify a future pandemic pathogen, we can develop vaccines for it in advance. But with new mRNA technology that allows vaccine development within days, there is no longer any advantage to developing the vaccine in advance. Some say that even if this research doesn’t help us develop a vaccine in advance, it can at least help us run a Phase 1 safety trial in advance, so that we don’t have to waste time running it after the pandemic has already started. But according to Esvelt, a Phase I trial would be combined with a Phase II trial if we were ever in a serious pandemic, which means there is no advantage to doing a Phase I trial in advance.

The second claim is that knowing about potential pathogens can help us develop broad-spectrum therapeutics or vaccines. These drugs can protect us not just against existing strains but future strains that haven’t yet crossed over into humans. Indeed, many studies have measured the coverage of broad-spectrum drugs against animal viruses that have not yet crossed over to humans (1,2,3,4,5). But when I looked into these studies more closely, most of the benefit could be achieved by using viruses that have already circulated in humans, which already span a similar breadth of the evolutionary tree.

Esvelt says that while there is some minor benefit to finding and sequencing more viruses in the spectrum (an activity he does not think is worth the risks), there is less advantage to characterizing and publishing how dangerous each of them is, the activity that he calls pandemic virus prediction. This type of activity doesn’t really tell us where to focus our broad-spectrum antiviral research. The really dangerous types of mutations can happen on multiple branches of the evolutionary tree, and are mostly independent of the ability of vaccines or antivirals to recognize the virus.

What can be done

To recap, well-meaning scientists are doing research of dubious value and unfathomable risk, publishing information about dangerous viruses the world has never seen, which thousands of people can assemble themselves. What can be done? In testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee last week, Esvelt laid out several steps. I will list a few here:

- Stop funding pandemic virus prediction research.

- Move oversight away from the funding agencies and towards regulators with security experience

- Cooperate with China. Use the Biological Weapons Convention to block this type of research.

- Prohibit DNA synthesis companies from shipping DNA with pandemic potential.

I hope that Congress will act promptly to implement these measures.