Teens, loneliness, and the social media paradox

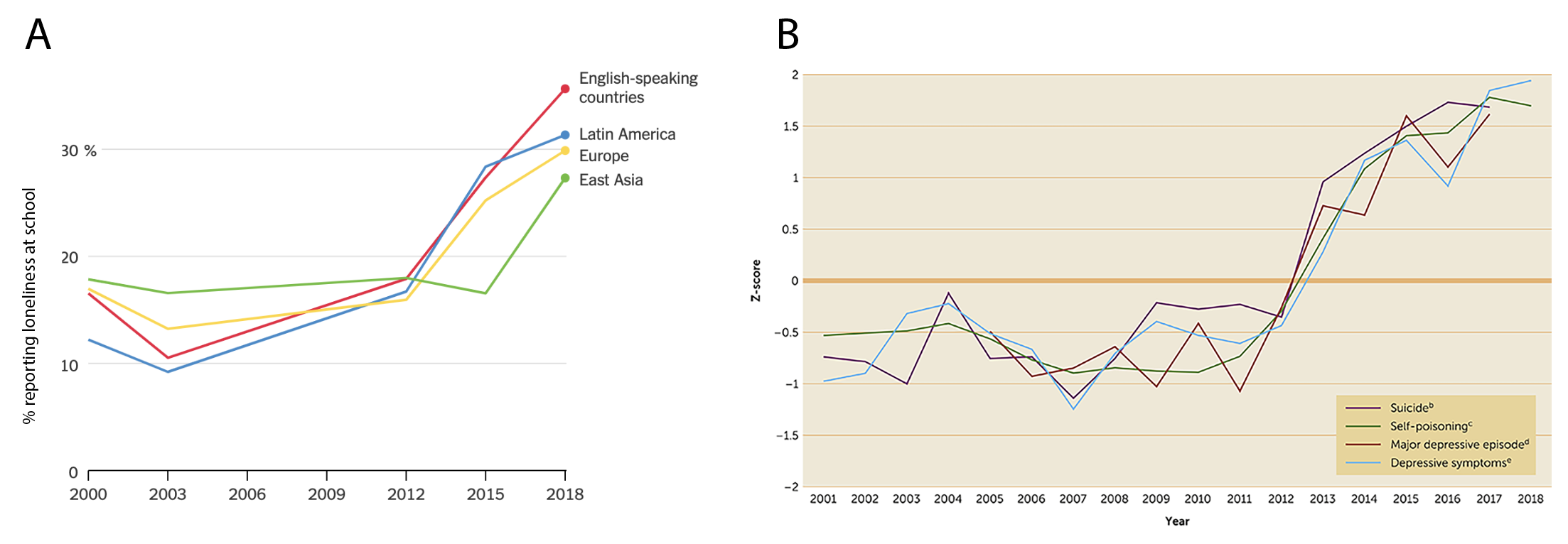

14 Aug 2021Starting around 2012, teen loneliness and depression increased dramatically. A good explanation is social media, which became more ubiquitous and addictive around that time. Teens now spend an average of seven hours per day online, not including time spent doing homework. Social media is simply a massive intervention in teen culture, and no other development has so profoundly changed the way teens socialize. When you consider widespread observations of how social media can drive envy, anxiety, and a manifest decline in in-person social skills, it is not surprising to see the rise of social media time-locked to changes in teen mental health.

Figure 1. A: share of students reporting high levels of loneliness at school (PISA, via Haidt and Twenge, 2020). B: indicators of poor mental health among U.S. girls and young women, 2001–2018 (CDC and other sources, via Twenge, 2020)

Recently, some researchers have begun to question this narrative. In one large study, Orben and Przybylski (2019) found that teens who used social media heavily were only slightly more likely to have poor mental health than those who used it lightly (but see Twenge et al. (2020)). Because of the weak individual-level correlation, the researchers concluded that the impact of social media was “too small to warrant policy change”.

I’m not sure I agree. It’s totally possible and indeed likely that social media has caused a major drop in teen well-being even though the cross-sectional data shows only weak correlations between social media use and well-being.

You might think that’s a paradox, but here are three simple ways it can happen.

Social media doesn’t make you unhappy directly. It makes you less fun, which makes everyone else unhappy.

The first mechanism is that while social media might not directly make you less happy, it degrades your in-person skills, making you less fun and less available to others. This in turn makes everyone else around you unhappy. And by the same token, since everyone around you is on social media, they also become less fun and less available, which makes you unhappy, regardless of how much social media you use. If this hypothesis is true, the paradox would be resolved. As economists might say, the negative impacts of social media are fully externalized.

Is there any evidence that social media reduces in-person social skills? Of course there is, just look around! Compare the social interactions you see today to any social interactions videotaped before the year 2000. Or compare the social skills of a Boomer to someone in Gen Z. The decline is undeniable.

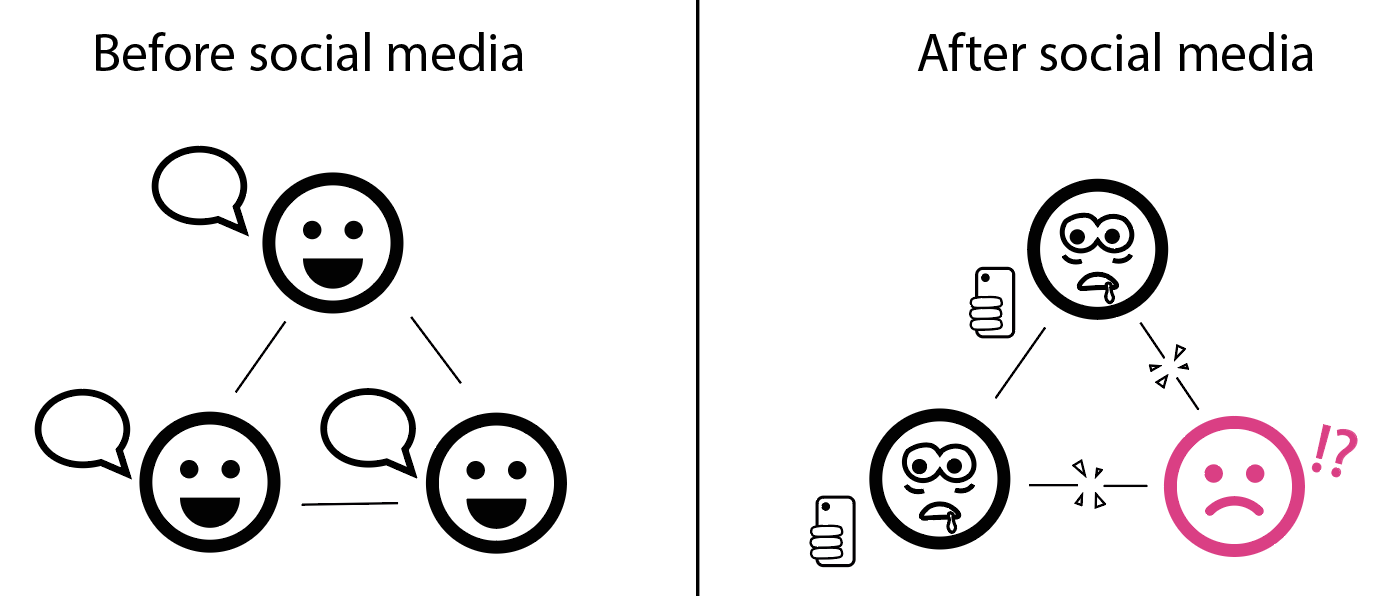

Social media is a trap

The second mechanism is that social media traps its users in an inferior equilibrium and punishes those who don’t use it. Because social media is where all their friends are, most teens have no choice but to use it. Unlike in the first hypothesis, social media makes them vaguely unhappy, but its addictive properties and network effects pull them in anyway. Meanwhile, a minority of teens do not use it, but they are also unhappy because they miss out on the center of social activity. Everyone is therefore less happy, and there is no individual-level correlation between the amount of social media use and happiness. If this hypothesis is correct, the paradox would be resolved.

Figure 2. Social media as a trap.

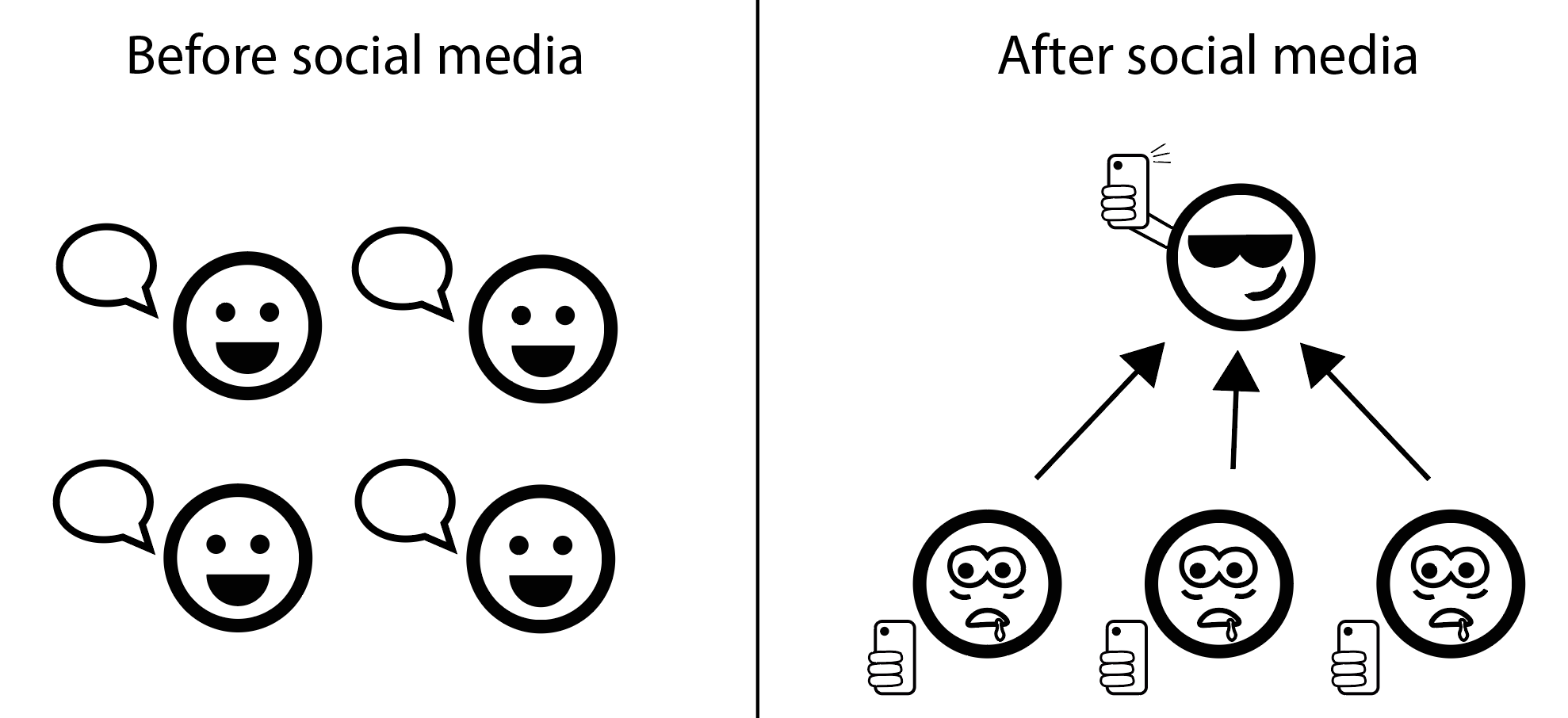

Social media makes the rich get richer and the poor get poorer

The third mechanism is that social media creates a small group of social “winners” who enjoy unprecedented attention, while everyone else gets left behind. Before social media, analog throughput constraints limited how much attention could be consumed by one person. With social media, those scaling constraints were lifted, and attention that otherwise would be shared within groups gets redirected to a small set of winners.

Because they like the attention, winners use social media just as much if not more than the non-winners, pushing the correlation between social media use and well-being in a positive direction. But because most people are non-winners, overall well-being is lower. This hypothesis, which would also resolve the paradox, is supported by the finding that “active” use of social media promotes well-being whereas “passive” use promotes the opposite.

Figure 3. Social media might make the rich get richer and the poor get poorer

Conclusion

I do not know which of these three mechanisms is correct, but I suspect that more than one may play a role. Either way, I am not persuaded by individual-level correlations between social media use and well-being. To me, the time series trends and common sense mechanisms are much more persuasive, and I’d be very interested in any future studies that explore these kinds of network-based hypotheses.