Autism, folic acid, and the trend without a blip

27 Jun 2021What are some ways to reduce the risk of autism? According to published research, one of the most powerful interventions is for mothers to take folic acid around the time of conception. A recent meta-analysis of 10 studies found that folic acid supplementation reduced the odds of autism by about 42%. A large cohort study from Norway found an odds reduction of 49%, and some studies have even found reductions of more than 80%. These are massive effects.

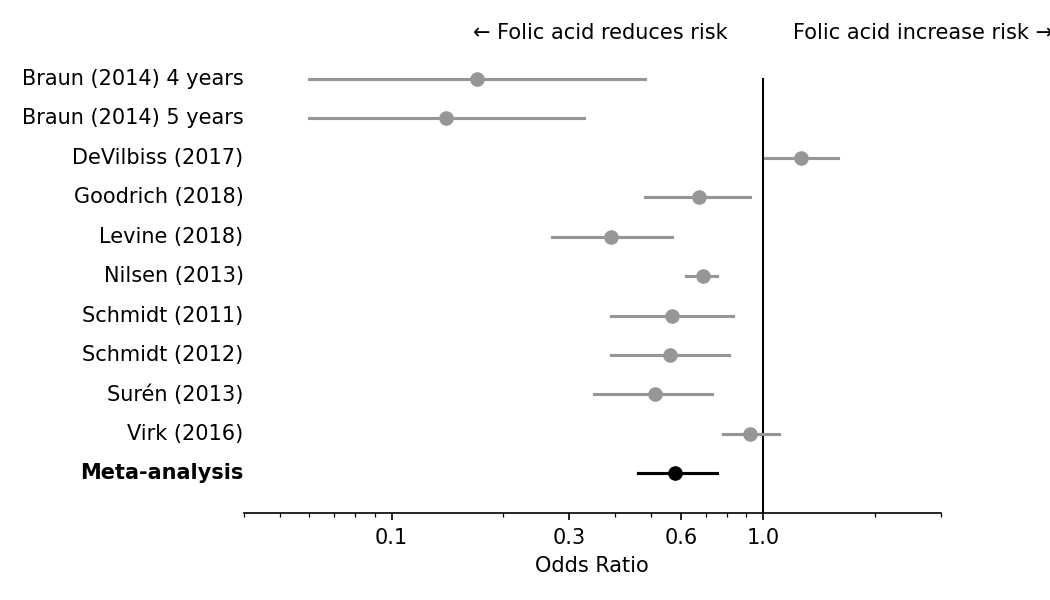

Figure 1. Reproduction of the forest plot from the Iglesias Vázquez meta-analysis of 10 studies.

While all the studies were observational, they all took care to control for maternal age, education, birth year, and other confounders. One study, which I will address in the comments below, found that the beneficial effect of folic acid is specific to people who have a gene variant that makes it hard to process folate. Another study found that folate receptor antibody concentrations are higher among children who have autism than controls.

The biological mechanisms for folic acid’s protective effect are plausible. Folic acid taken near conception is known with certainty to reduce neural tube defects. Periconceptual folic acid intake increases DNA methylation of specific gene regions of the child, and DNA methylation is known to be abnormal in autism. Taking all the evidence together, one review from 2014 concluded that of all nutritional factors for autism, folic acid likely has the “strongest” impact.

The trend without a blip

These are promising claims. But how much can they be believed? To dig deeper, let’s go back to something that happened in 1997.

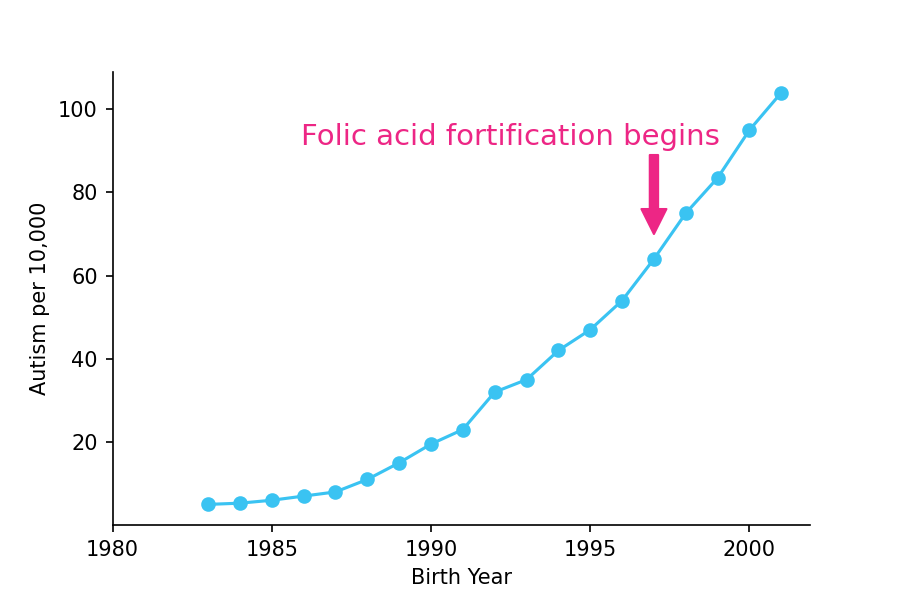

Because folic acid taken near conception is known to reduce the risk of neural tube defects, the FDA in 1997 started to mandate folic acid fortification in cereal grain products. This caused a sharp increase in average folic acid intake in the United States. As intended, fortification also caused a sharp decrease in neural tube defects, with properly estimated reductions coming in at 40%.

But what about autism? If the literature is correct, and folic acid really causes a 42% reduction in autism, we should see a sharp decrease in autism diagnosis for births starting in 1997. Instead, autism rates continued to increase at exactly the same rate they had before. There is nothing in the data to suggest even a small drop in autism around the time of folic acid fortification.

Figure 2. Trends in autism in 9-year olds in the United States plotted against birth year. Adapted from Nevison (2014), with data obtained from the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) database.

Some might say that autism trends were increasing at the time because of better diagnosis, and that the trend would have been even stronger if it weren’t for folic acid fortification. But the 1997 fortification mandate was a sharp discontinuity. If it helped, you would still expect to see a cliff-like “drop” in the curve at that time, followed by a resumption of the trend.

Others might say that the 1997 fortification didn’t provide enough folic acid to meaningfully decrease the rates of autism. And indeed, the fortification was only responsible for an average increase of 100-250 micrograms per day (1, 2), which is less than the high 800 microgram doses found in many supplements. Given that most medical dose response curves are sublinear, one might expect the 100-250 microgram dose to provide about half the benefit, or a 20% reduction in risk. Such a reduction should be dramatically apparent in the time series around 1997. Instead, the actual time series doesn’t even show a blip. Even if you conservatively assume a linear dose response curve, a 100-250 microgram increase should still cause a 5-13% reduction in autism rates, but nothing remotely like that is visible in the data.

Could it be a confounder?

If folic acid fortification starting in 1997 failed to cause any change in autism trends, why did so many studies find a strong relationship between folic acid intake and autism?

One obvious explanation is confounders, a prospect that researchers in the field candidly acknowledge. For example, the mothers who took folic acid also tended to take other vitamins, and perhaps one of those vitamins is the true causal factor. Frustratingly, the literature is mixed on whether the benefits are driven by the folic acid or the other vitamins. One large study concluded it was the multivitamins rather the folic acid. Another large study concluded it was the reverse. I’ve read both of those papers fairly closely and I can’t figure out a good explanation for the discrepancy.

If other vitamins aren’t the answer, maybe there is another confounder that we are simply not aware of. One clue that something else is going on can be found in Levine (2018), which reported that folic acid taken 2 years before conception (but not anytime closer to conception) reduced autism just as much as folic acid taken directly prior to conception! If true, that effect is likely driven by something else the mothers are doing, rather than a folic acid effect that persists for two years after supplementation has stopped.

How good is this literature, really?

The other possibility is that this subfield has the same high levels of publication bias and questionable research practices, inadvertent or otherwise, that so many other medical subfields have. Some literatures have it so bad that they are driven entirely by p-hacking and publication bias, with zero underlying true effect.

It’s tough to say whether the same thing is happening with autism and folic acid, and I don’t want to malign all these studies. But there are a few hints in the data that something is amiss.

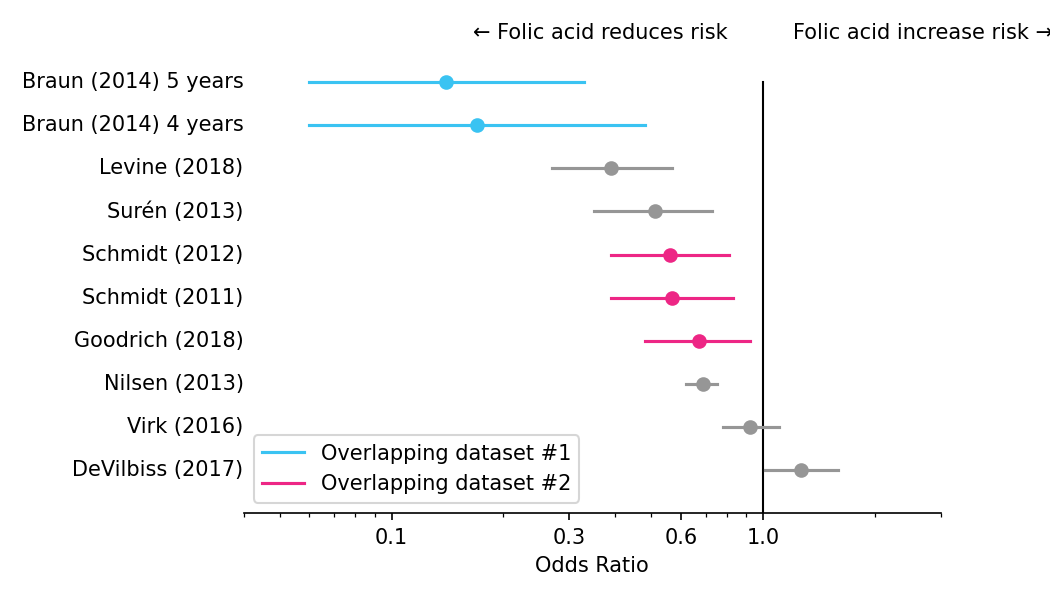

Let’s sort the studies in the meta-analysis by the size of their effects. As you can see in Figure 3, the studies with the largest benefits of folic acid also had the largest error bars. The studies with weaker or null effects had smaller error bars and larger sample sizes. This trend is a hallmark of publication bias. With enough research degrees of freedom, it’s just a lot easier to find something in a low-powered study than a high-powered study.

Figure 3. Alternative display of forest plot from the meta-analysis of 10 studies, with studies sorted by effect size, and shared coloring (blue or pink) if using overlapping or similar datasets. Schmidt (2011), Schmidt (2012), and Goodrich (2018) all used overlapping datasets. Braun (2014) was a single study, although it was included in the meta-analysis as two separate findings. Suren (2013) and Nilsen (2013) are sufficiently different that I have left them as gray. Nevertheless, they were conducted by the same research group, and their data was sampled from similar populations (Norwegian mothers during the same time period).

Moreover, many of the studies that found a beneficial effect used highly overlapping datasets, which I’ve indicated with color coding. This means that while many studies found a beneficial effect of folic acid, far fewer datasets showed a beneficial effect. It also means that when research groups found a beneficial effect in a dataset, they were likely to publish again from the same dataset. When research groups did not find an effect, they only published once. I wonder how many groups, upon finding no effect, even published at all?

Overall, I am skeptical that periconceptional folic acid has any effect on autism. There is likely residual confounding, and I suspect there is publication bias as well. The claims are reminiscent of other claims in the vitamin literature, which has a long history of large effects in observational studies that disappear when a randomized trial is finally run.

What does this mean for you?

In line with the CDC, those who are considering becoming pregnant should still take folic acid for its protective effects against neural tube defects, even if it might not have any effect on autism. And given that folic acid’s association with autism may be due to confounders, those considering pregnancy may want to just copy whatever else the mothers who take folic acid are doing.

As for the research field, my strong belief is that more medical research should be pre-registered, and funding agencies should fundamentally reshape science incentives.