Contagiousness sensitivity: The metric that could control the pandemic

29 Nov 2020Disclaimer: I’m not a medical professional, but I’ve been working closely with testing experts since July.

Until vaccines are widely adopted, rapid antigen tests are one of our best hopes for controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. If used widely, these inexpensive tests could massively drive down infections.

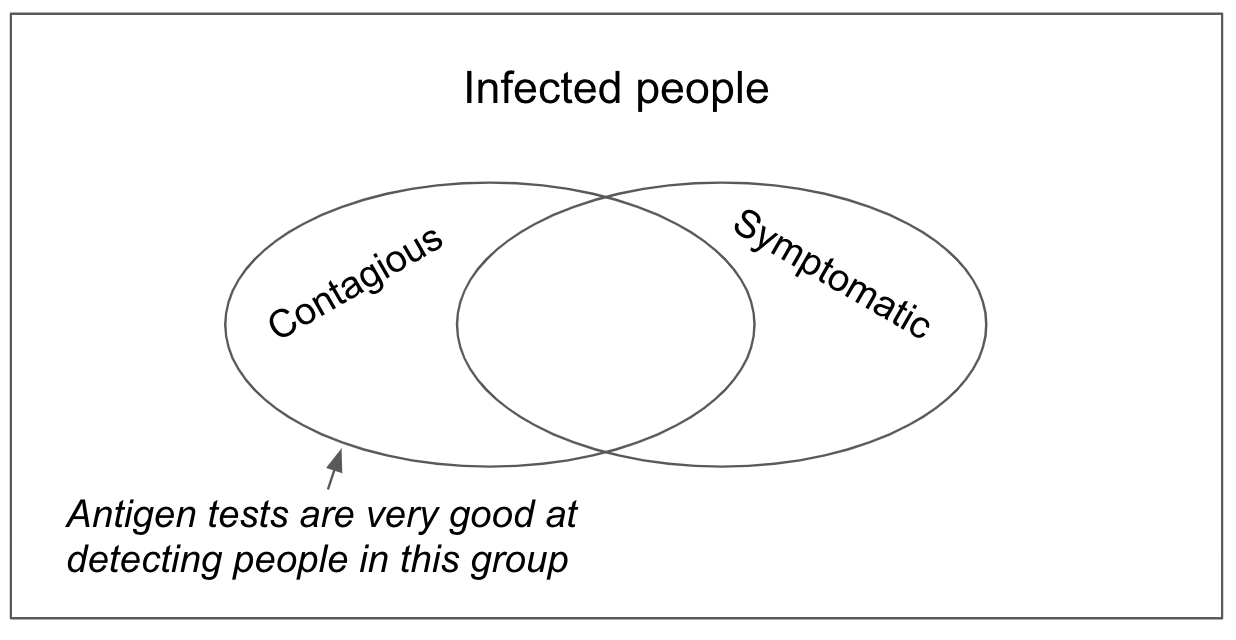

Antigen tests work because they can identify people who are contagious. Knowing you are contagious lets you isolate yourself before you infect others.

Most antigen tests have very high contagiousness sensitivity, defined as the percentage of contagious people that the test detects. This is a crucial metric for public health.

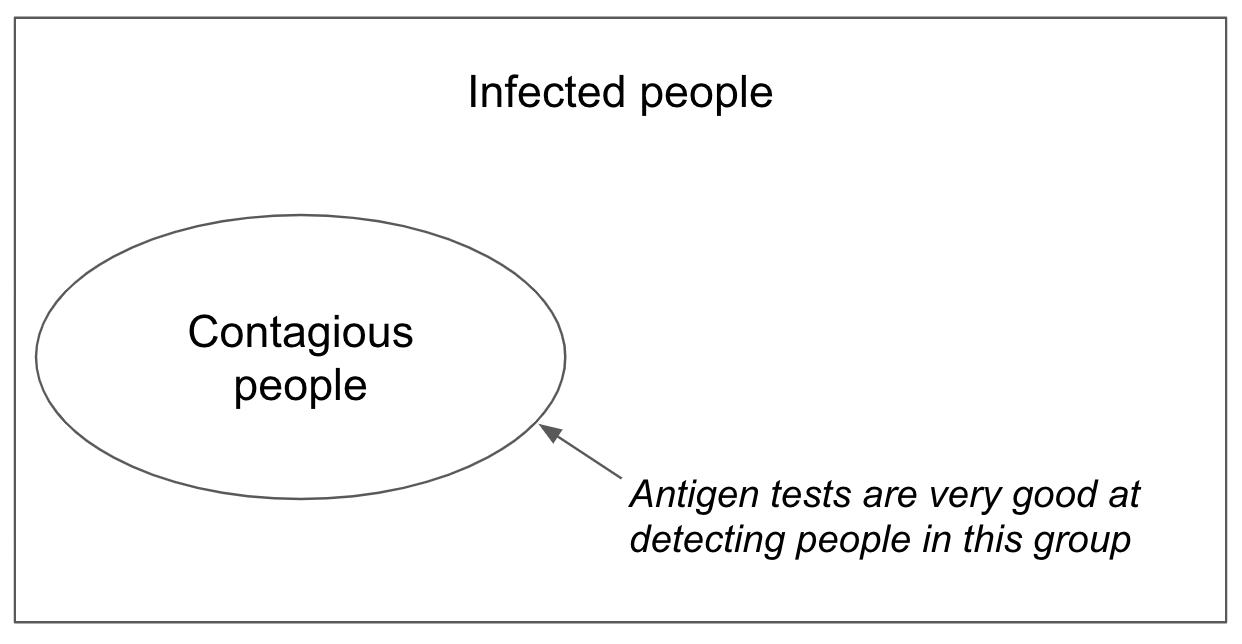

Figure 1. Venn diagram showing that most infected people are not likely contagious

There is another metric, however, called diagnostic sensitivity. It is defined as the percentage of infected people a test detects. While useful for medical purposes, diagnostic sensitivity is far less useful for public health. That’s because it includes many people who have trace viral RNA fragments that can remain for weeks after they have stopped being contagious. In some populations, antigen tests may have >95% contagiousness sensitivity, but only 40% diagnostic sensitivity. When it comes to stopping spread of the virus, the number that matters is the 95%, not the 40%. Almost everyone the antigen test “misses” is no longer contagious.

Although easy access to antigen tests was proposed very early in the pandemic, we still don’t have it in the US. The few tests available are only approved for symptomatic use cases, even though they would be most useful for preventing asymptomatic spread. The only at-home test requires a doctor’s prescription.

Why has the US failed to provide ready access to antigen tests? There are a variety of reasons. But a core reason, underlying most of the others, is that many medical experts and regulators are hesitant to treat contagiousness sensitivity as a formal metric, even though they informally acknowledge it is reasonable and practical. In official correspondence, medical experts have preferred the more precise but much less relevant diagnostic sensitivity metric. This practice has led to confused dialogue, a regulatory system that uses inappropriate standards to assess rapid tests, and ultimately a pandemic that is much worse than it could have been.

Contagiousness sensitivity: Yes, it’s a good enough metric.

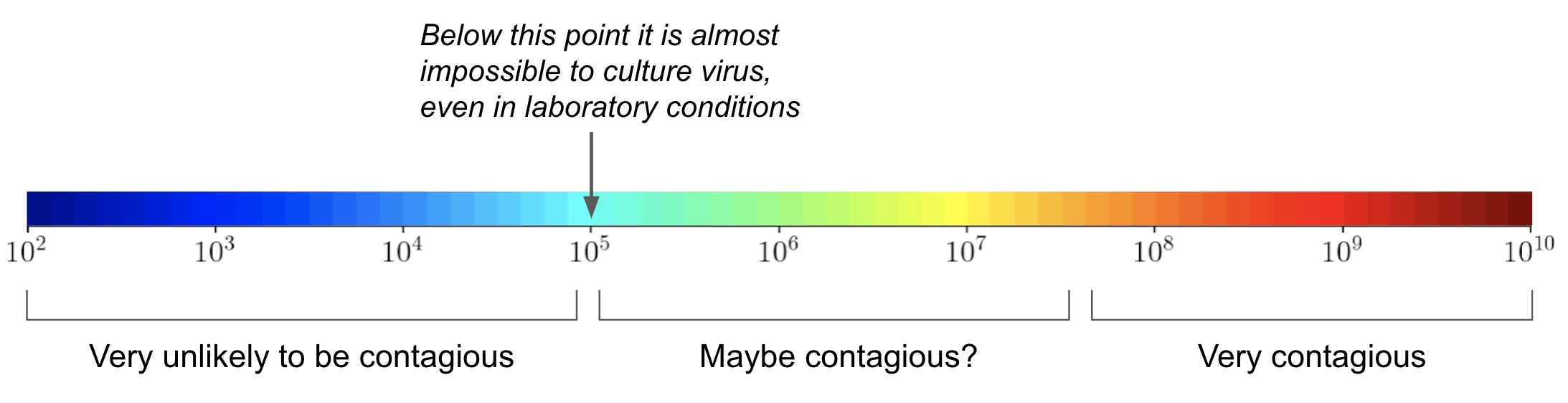

What makes someone contagious? There are several factors, but a reasonable definition is that someone is contagious if their viral count is greater than \(10^5\) cp/mL. Most contagious people have viral counts of around \(10^7\) to \(10^{10}\) cp/mL. People may be slightly contagious with viral concentrations tens of thousands of times lower, like \(10^5\) or \(10^6\) cp/mL. But as a rule of thumb, people are not contagious if their viral concentration is less than \(10^5\) cp/mL.

Figure 2. Likely levels of contagiousness as a function of viral concentration (cp/mL)

Critics say that we can’t be certain of this cutoff. What if the cutoff is actually \(10^4\) or \(10^6\)? What if there are other factors besides viral count? What if the same viral count is more contagious when the virus is spreading than when it’s being removed?

The critics aren’t wrong. But in a public health crisis, we cannot afford this level of precision – it sets up the perfect as the enemy of the good.

What follows is evidence that contagiousness can be reasonably and approximately defined as a viral count > \(10^5\).

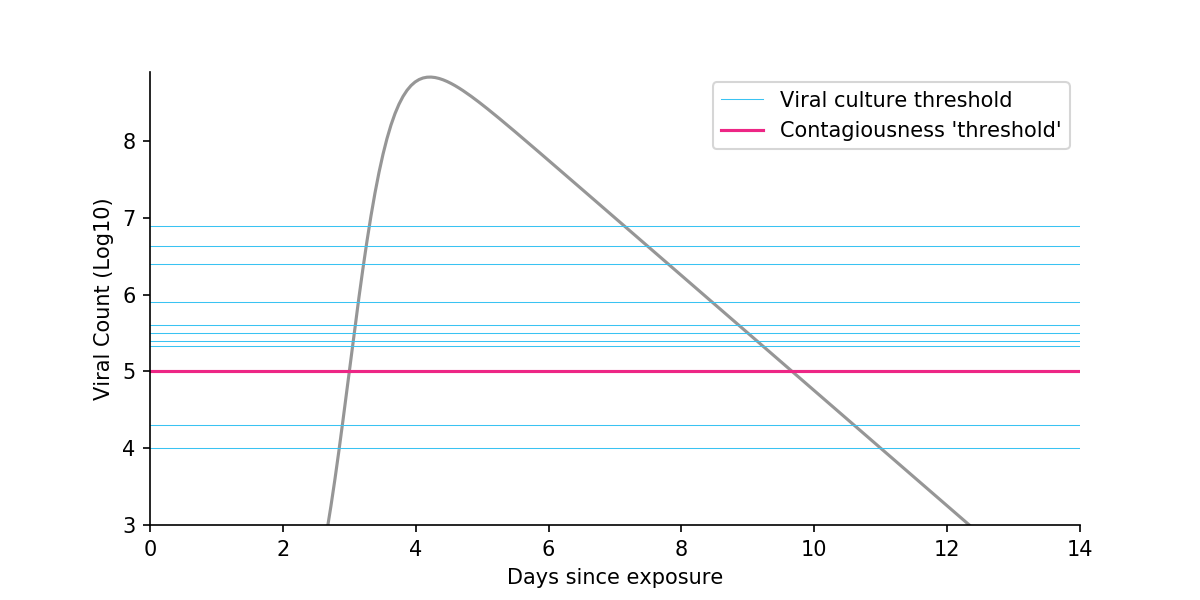

- In ideal laboratory conditions, most studies cannot culture the virus from samples where viral count is < \(10^5\) cp/mL. Only two studies have been able to do this at \(10^4\) cp/mL, and they could do so only in a very small fraction of samples. The plot below shows this on a log scale, where each increment represents a 10x increase in viral count.(cp/mL)

Figure 3. Viral kinetics in a typical COVID-19 case. Each blue line corresponds to a study and shows the threshold at which no or virtually no virus could be cultured in laboratory conditions. The vertical axis is on a log scale, where each increment represents a 10x increase in viral count. Viral kinetics from Larremore et al., 2020.

- Shifting from a log to a linear scale shows that virtually all viruses live in samples far above the \(10^5\) cutoff. So even if you think something like \(10^4\) would be a better cutoff, the impact on the total amount of virus above threshold is negligible. (Note: I am not claiming that contagiousness is linearly related to viral count, only highlighting that the log scale can distort how people think.)

Figure 4. Shifting from a log scale to a linear scale

- A study in hamsters showed they can infect each other if their virus can be cultured but not when it can’t. In fact, hamster-to-hamster transmission didn’t even happen at \(10^6\) cp/mL, suggesting that a \(10^5\) cutoff is conservative.

Is this evidence perfect and incontrovertible proof that no one with a viral load less than \(10^5\) could ever infect someone? No, it is not. Is it enough for a reasonable person to adopt contagiousness sensitivity with a cutoff of \(10^5\) as a useful metric? Yes, it is.

Using the wrong metric leads to bad outcomes

While practically useful, contagiousness sensitivity does not have official recognition in medical and regulatory circles. As a result, much of the conversation falls back on the irrelevant diagnostic sensitivity metric, which leads to confusion and inappropriate regulation.

Let’s look at two examples.

Journalism

A recent New York Times article headlined “A Rapid Test Falters in People Without Symptoms” highlighted low diagnostic sensitivity in antigen tests (30% in some populations!). Only after 21 paragraphs did the article mention the much more relevant contagiousness sensitivity metric, which showed strong real world performance at 85%. By highlighting the irrelevant metric rather than the relevant metric, the article gave readers the impression that antigen tests are inaccurate. In fact, antigen tests are accurate – for the job that they are intended to do.

Why did the journalist wait so long to introduce the contagiousness sensitivity metric? Because of concerns that appear overly academic. “There is no universal ‘magic-number cutoff’, one researcher was quoted as saying. Failure to culture the virus is not a “guarantee” of lack of contagiousness, said another.

Both of these critics are technically correct! It’s just that the level of precision they are demanding isn’t inappropriate for a public health testing goal. In public health, a practical but imprecise metric is better than a precise but irrelevant metric. Measures that are merely reasonably good, like vaccines and masks, can help break transmission chains.

FDA Regulations

According to the diagnostic sensitivity metric, antigen tests are less sensitive in asymptomatics than in symptomatics. Because the FDA uses this metric, they have not approved any antigen tests for asymptomatic use.

From a public health point of view, this makes little sense. To control the virus, you need to identify contagious individuals. Symptomatic people tend to have more virus than asymptomatic people, so it’s no surprise that antigen tests have higher diagnostic sensitivity among symptomatic people. What matters to public health is contagiousness sensitivity, which is equally high in both asymptomatics and symptomatics (95% in the most recent study)! In other words, if a test is good at detecting contagious symptomatics, it will also be good at detecting contagious asymptomatics.

Figure 5. Venn diagram showing that most asymptomatic infections are not contagious, and yet a large fraction of contagious people are asymptomatic.

Because the FDA does not use contagious sensitivity, it overlooks this critical insight. Manufacturers are still required to submit data separately for symptomatics and asymptomatics. Because it is arduous to collect data for asymptomatics (it is hard to track down positive asymptomatics), most manufacturers apply only for the symptomatic use case.

The FDA could greatly speed up the process and justifiably approve antigen tests if they based their decisions on contagiousness sensitivity, a step which would dissolve the unnecessary requirement to show separate data for symptomatics and asymptomatics.

A plea for the medical community

If there are any medical experts reading this, my plea to you is to help make contagiousness sensitivity a formal metric in your profession. If you are a scientist, use this metric in your papers (many already are). And if you are a regulator, consider using this metric as your standard for public health tests.

Special thanks to Jon Frankle and Jonas Binding for comments on an earlier draft.