Why low sensitivity antigen tests are better than slow PCR tests

15 Jul 2020UPDATE: After I posted this, I came across a recent preprint from Larremore et al. that makes this point much better than I do. The preprint emphasizes that antigen tests have high sensitivity when viral load is high, corresponding to when people are contagious. See rapidtests.org for more info.

If we want to reopen schools and offices, we need to do so safely. According to Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Romer, the best way is with frequent and regular testing of asymptomatic students and employees. Catching infections early can stop the spread before it starts.

Much of the discussion about testing has centered on PCR, a relatively expensive method that is vulnerable to multiple supply chain bottlenecks and is generally hard to scale up. Test samples must be sent to a central laboratory and then passed through expensive machines, a process that is currently taking 5-7 days, and in some places as high as 10-13 days. Efforts are being made to speed this up via pooling, but the operational complexity of PCR makes it likely that there will always be at least a few days of delay.

A less talked about alternative to PCR is called antigen tests. These tests are much cheaper than PCR, with estimates ranging between $1 and $10 per test, compared to $50 for PCR. More importantly, they can return results in just 15 minutes, without any need to send samples to a central lab.

Since antigen tests are far cheaper and faster than PCR, why are we not massively investing in them?

The usual answer is test sensitivity. SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests have a sensitivity of about 85-90%, meaning that only 85%-90% of true cases will be detected as such. And those are optimistic estimates reported by test manufacturers. For influenza, the CDC reports that antigen tests have a sensitivity of 50-70%. This is much lower than PCR tests, which have a sensitivity as high at 98%.

Some doctors view the low sensitivity as an insurmountable hurdle. “It won’t work”, said one doctor. “A misdiagnosis is worse than no diagnosis”, said another.

I am not sure I agree, at least when it comes to mass testing of asymptomatic individuals. In this blog post I will show, via both simulations and analytical arguments, that the low sensitivity of antigen tests is a much better problem to have than the long delay of a PCR test.

Simulations

To test this hypothesis, I built an agent-based SIR model that includes testing and quarantining. I make the following key assumptions:

- Population of 200 students

- Using a rotation system, each student is tested once every K days.

- Students go into a 14 day quarantine if they get positive test results.

- In addition to intra-school infections, each student has a chance of getting infected by someone outside the population.

I simulated two different scenarios.

- Regular PCR testing (sensitivity of 98%, testing delay of 5 days)

- Regular antigen testing (sensitivity of 75%, no testing delay)

For comparison, I also modeled a “best case scenario”, where no intra-school infections occur, and a “worst case scenario”, where there is no testing or quarantining at all.

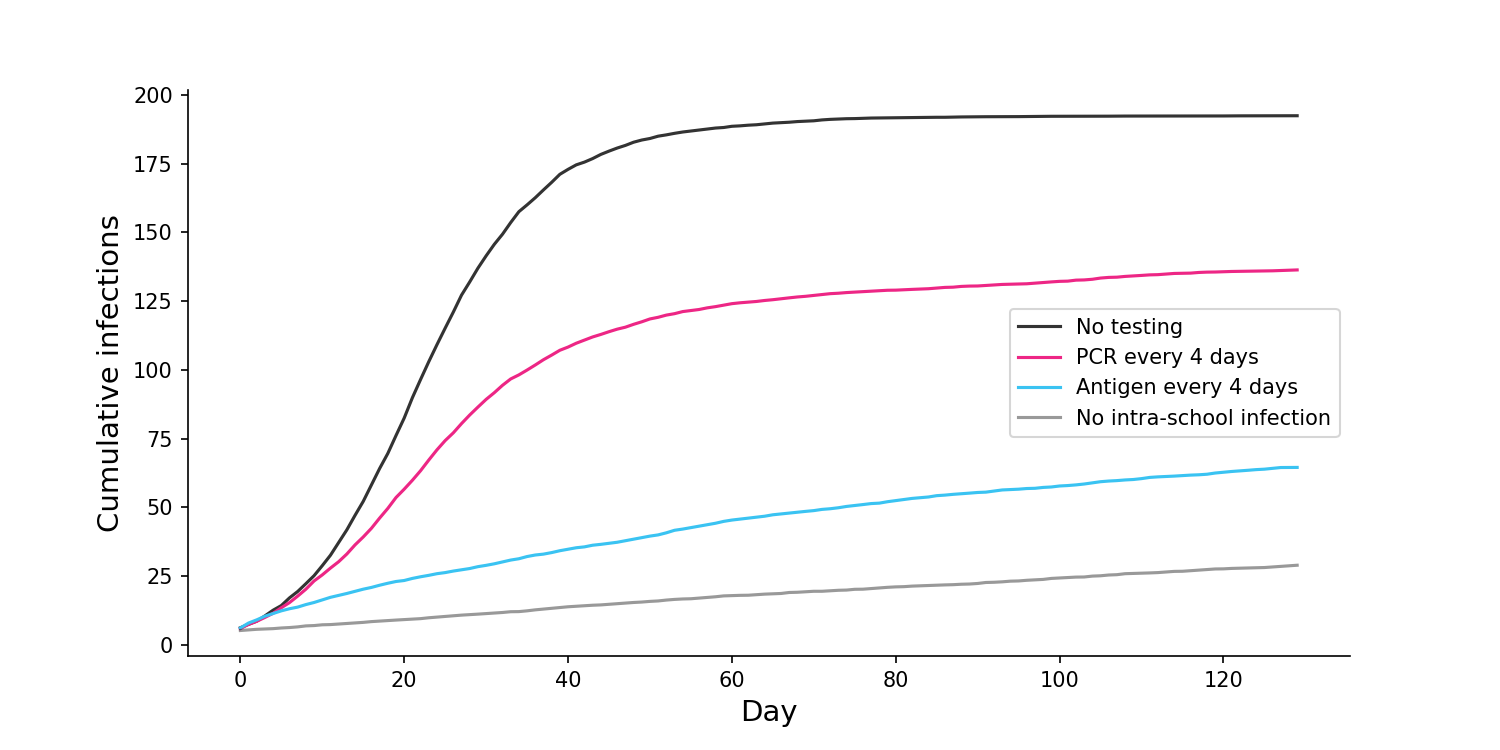

Assuming that each student is tested once every 4 days, I find that the cumulative number of infections is far lower if we do regular antigen testing than if we do regular PCR testing.

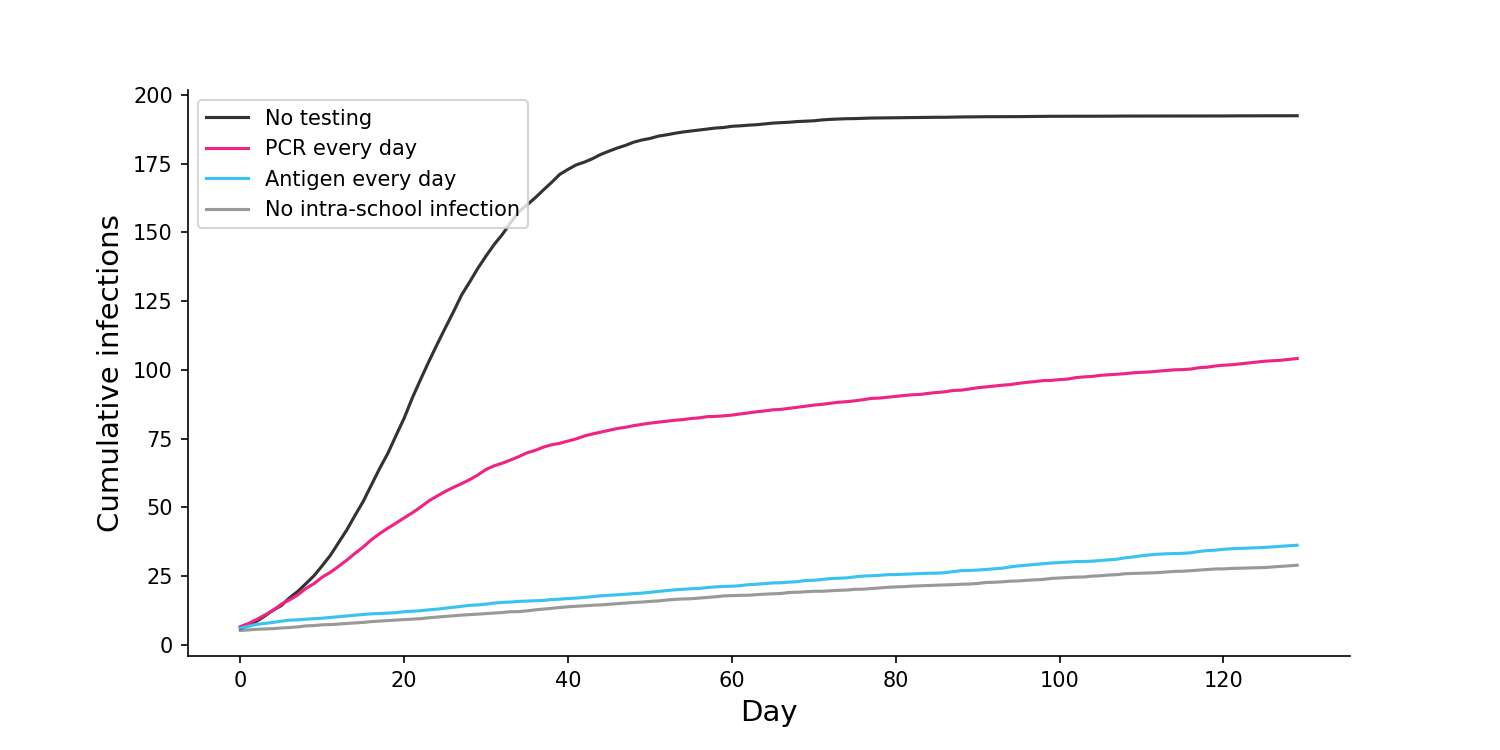

If we change the frequency of testing to once every day, antigen testing is able to achieve close to best case results, with almost no intra-school infections. Meanwhile, daily PCR testing still results in a large number of infections.

This seems very important. Not only are antigen tests cheaper than PCR, they are also more effective in a mass testing regime. Further simulations in my notebook show that the superiority of antigen tests is maintained even for much lower sensitivities.

Why is low sensitivity better than slowness?

Maybe you don’t believe my simulations, so here’s an analytical argument instead. Imagine you test people every day using a 75% sensitive antigen test. If someone is infected, they will probably find out immediately. There is a smallish chance they will first find out after a day, and a very small chance it will take longer than that. On average they will find out after 0.33 days, which is much faster than a typical PCR test. In general, for a sensitivity of \(s\), daily antigen test participants will find out after an average of \(d\) days, where \(d\) is defined as:

\[d = \sum_{t=0}^{\infty}{(1-s)^t s t}\]which converges to

\[d = \frac{1-s}{s}\]For any reasonable value of \(s\), \(d\) will be quite low. Here’s a striking example. If you test people every day, a test with 50% sensitivity and no delay is equivalent to a test with 100% sensitivity and a 1-day delay!

This analysis assumes that \(s\) is fixed across time and individuals, an assumption I’ll address in the FAQ, below.

FAQ:

Q: What is your main conclusion from this analysis?

A: For mass testing of asymptomatic individuals in schools and offices, antigen tests are cheaper and more effective than PCR tests.

Q: Have other people come to this conclusion?

A: Yes. After writing this blog post, I came across two recent pre-prints.

- Larremore et al. shows that sensitivity is less important than testing delays. It comes with a wonderful interactive calculator.

- Paltiel et al. show that sensitivity is less important than test frequency.

Q: Are you arguing that antigen tests should always replace PCR?

A: No, I’m only suggesting it for mass testing of asymptomatic individuals. If a symptomatic person comes into a doctor’s office a PCR test would make sense, since sensitivity becomes more important and cost becomes less important.

Q: What if the antigen test has a much lower sensitivity for certain individuals, who will therefore remain undetected?

A: Low sensitivity for these individuals is likely due to low viral load, which most researchers believe means they will not be very infectious. That said, if would be really good if we could get more research on this, since it’s an important question.

Q: What if the sensitivity of the antigen test is especially low at the start of infection?

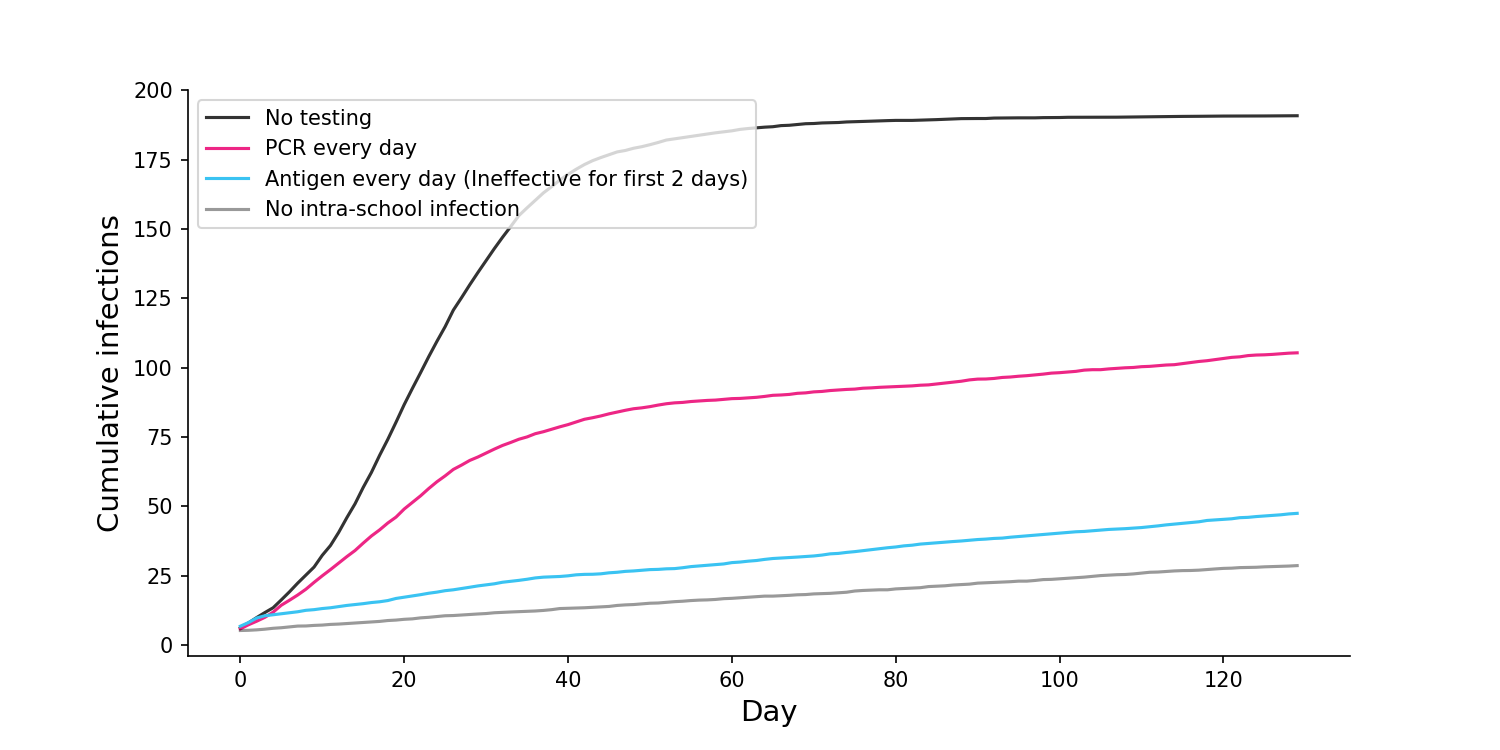

A: Another good question. As with the previous answer, this period of low sensitivity would likely be to due low viral load, when the individual is less infectious. Furthermore, the period where PCR tests can detect the virus while antigen tests cannot is probably only 24 hours. But even if we assume the individual is just as infectious during this early period, the antigen test still remains superior. To estimate this, I ran simulations where antigen tests were completely ineffective for the first two days of infection, a conservative assumption. Even with this conservative constraint, and even assuming the individuals are fully infectious during this period, antigen tests still outperformed PCR.

Q: What if the false negatives cause riskier behavior?

A: It’s possible that people might exhibit more risk after a false negative antigen test than after taking a PCR test and having to wait. However, this risk can be minimized by (a) educating people about sensitivity and (b) pairing the testing regime with other measures like masks and social distancing.

Q: Do antigen tests require those invasive pharyngeal swabs that go deep up your nose?

A: Not necessarily. While Quidel and Becton Dickinson are producing pharyngeal swab antigen tests, another company called OraSure is producing a saliva test. Will a saliva test be as accurate as a pharyngeal swab test? The evidence is mixed, with some studies suggesting it will be less accurate and others suggesting it will be more accurate (1, 2, 3).

Q: I heard that SONA has an antigen test with 96% sensitivity. This sounds super promising!

A: This statistic is a bit misleading. The positive samples were generated in a laboratory. When antigen tests are done in real world clinical settings, the sensitivity is lower.

Q: Will we ever get a test that is both fast and sensitive?

A: The New York Times had a great article last week on new types of point-of-care tests that are being developed, including HP-LAMP and SHINE. These seem promising, although they are in an earlier stage of development than antigen tests, which already have several companies producing tests.

A special thanks to Antonio Regalado and Alan Wells for help answering some questions during my research.