Using your ears and head to escape the Cone Of Confusion

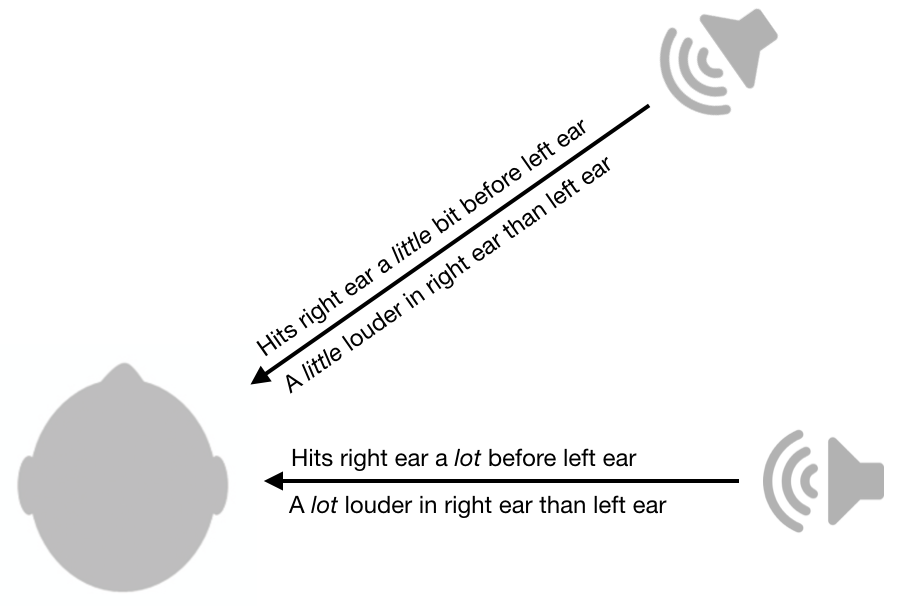

06 Aug 2018One of coolest things I ever learned about sensory physiology is how the auditory system is able to locate sounds. To determine whether sound is coming from the right or left, the brain uses inter-ear differences in amplitude and timing. As shown in the figure below, if the sound is louder in the right ear compared to the left ear, it’s probably coming from the right side. The smaller that difference is, the closer the sound is to the midline (i.e the vertical plane going from your front to your back). Similarly, if the sound arrives at your right ear before the left ear, it’s probably coming from the right. The smaller the timing difference, the closer it is to the midline. There’s a fascinating literature on the neural mechanisms behind this.

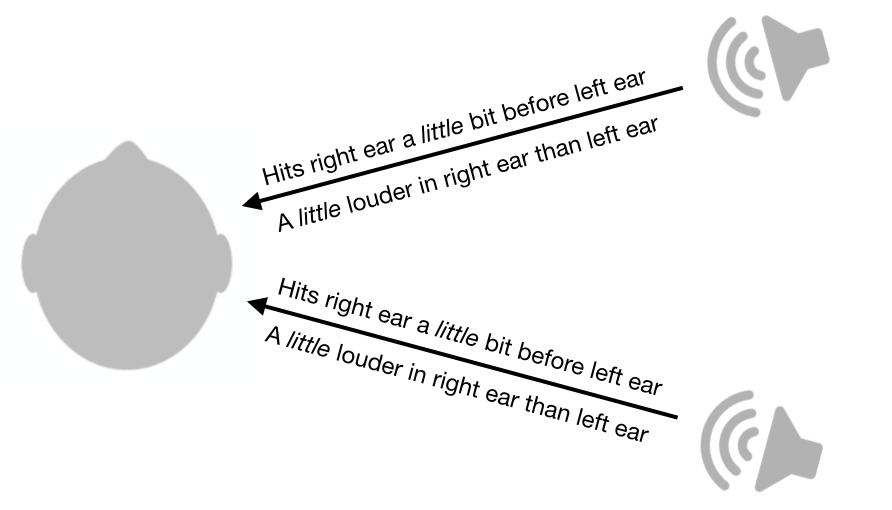

Inter-ear loudness and timing differences are pretty useful, but unfortunately they still leave a lot of ambiguity. For example, a sound from your front right will have the exact same loudness differences and timing differences as a sound from your back right.

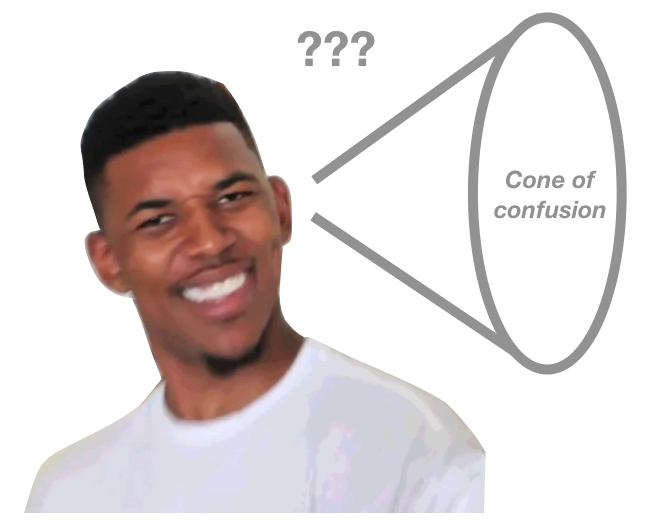

Not only does this system leave ambiguities between front and back, it also leaves ambiguities between top and down. In fact, there is an entire cone of confusion that cannot be disambiguated by this system. Sound from all points along the surface of the cone will have the same inter-ear loudness differences and timing differences.

While this system leaves a cone of confusion, humans are still able to determine the location of sounds from different points on the cone, at least to some extent. How are we able to do this?

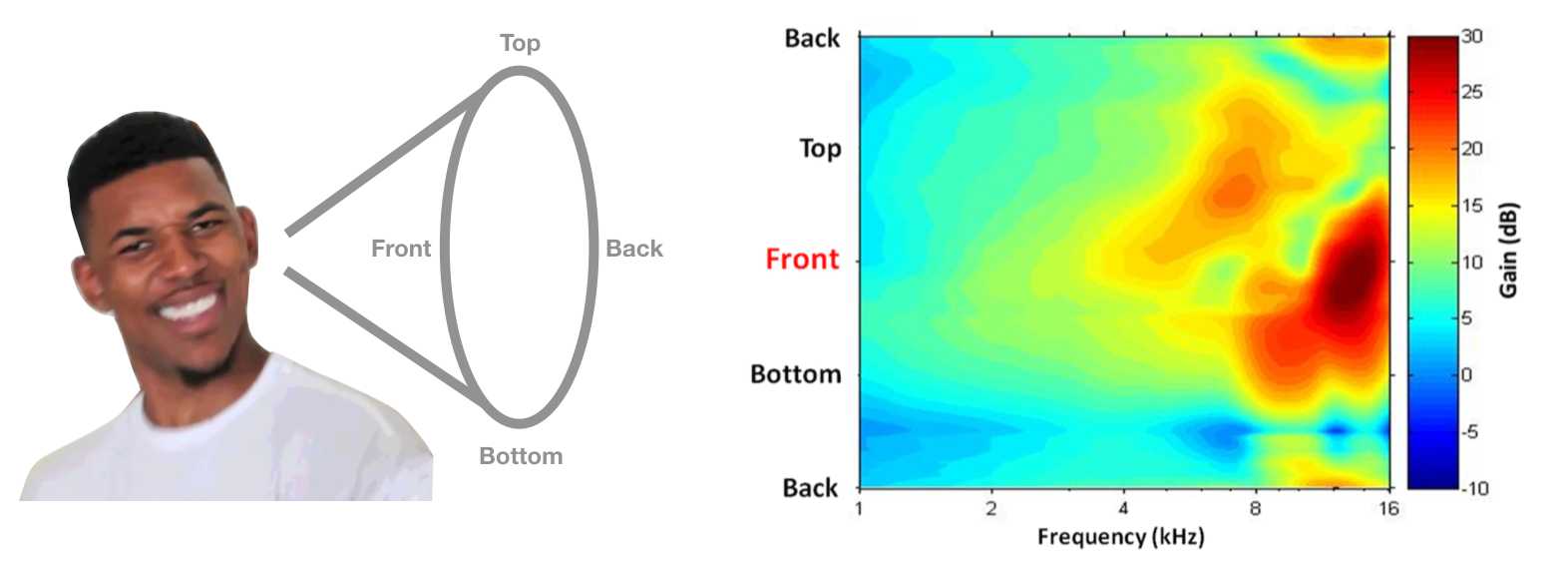

Amazingly, we are able to do this because of the shape of our ears and heads. When sound passes through our ears and head, certain frequencies are attenuated more than others. Critically, the attenuation pattern is highly dependent on sound direction.

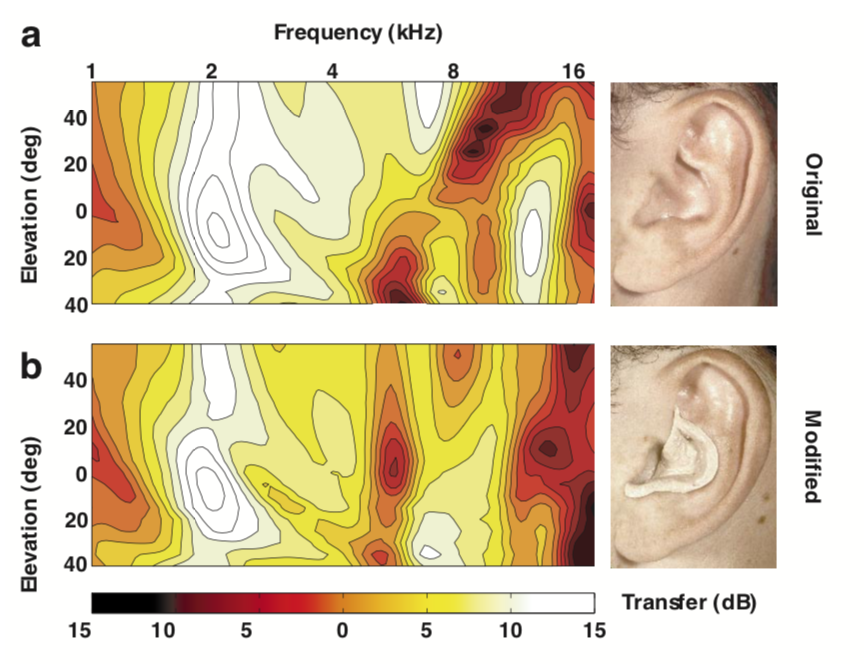

This location-dependent attenuation pattern is called a Head-related transfer function (HRTF) and in theory this could be used to disambiguate locations along the cone of confusion. An example of someone’s HRTF is shown below, with frequency on the horizontal axis and polar angle on the vertical axis. Hotter colors represent less attenuation (i.e. more power). If your head and ears gave you this HRTF, you might decide a sound is coming from the front if it has more high frequency power than you’d expect.

HRTF image from Simon Carlile’s Psychoacoustics chapter in The Sonification Handbook.

This system sounds good in theory, but do we actually use these cues in practice? In 1988, Frederic Wightman and Doris Kistler performed an ingenious set of experiments (1, 2) to show that that people really do use HRTFs to infer location. First, they measured the HRTF of each participant by putting a small microphone in their ears and playing sounds from different locations. Next they created a digital filter for each location and each participant. That is to say, these filters implemented each participant’s HRTF. Finally, they placed headphones on the listeners and played sounds to them, each time passing the sound through one of the digital filters. Amazingly, participants were able to correctly guess the “location” of the sound, depending on which filter was used, even though the sound was coming from headphones. They were also much better at sound localization when using their own HRTF, rather than someone else’s HRTF.

Further evidence for this hypothesis comes from Hofman et al., 1998, who showed that by using putty to reshape people’s ears, they were able to change the HRTFs and thus disrupt sound localization. Interestingly, people were able to quickly relearn how to localize sound with their new HRTFs.

Image from Hofman et al., 1998

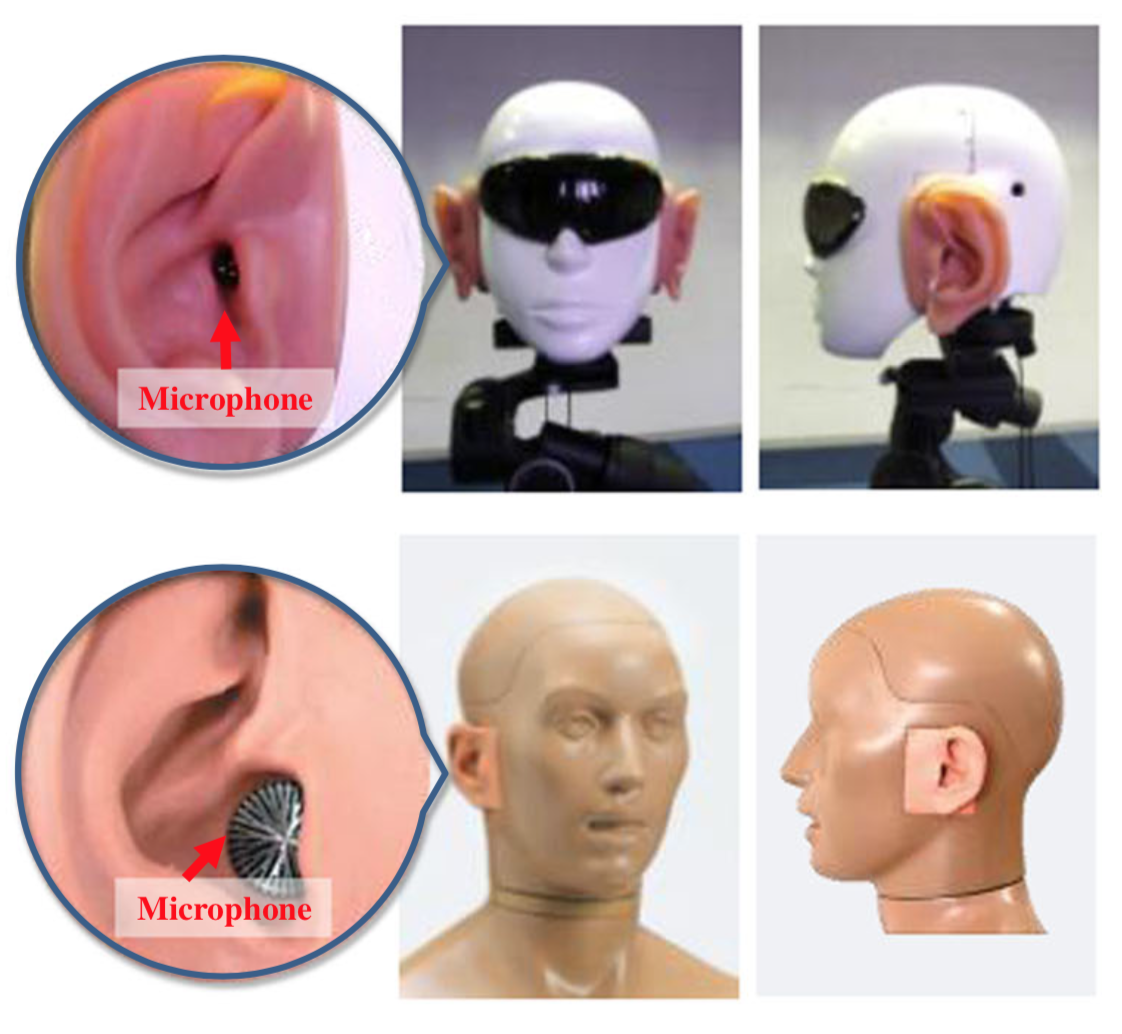

A final fun fact: to improve the sound localization of humanoid robots, researchers in Japan attached artificial ears to the robot heads and implemented some sophisticated algorithms to infer sound location. Here are some pictures of the robots.

Their paper is kind of ridiculous and has some questionable justifications for not just using microphones in multiple locations, but I thought it was fun to see these principles being applied.