Religions as firms

02 Dec 2017I recently came across a magazine that helps pastors manage the financial and operational challenges of church management. The magazine is called Church Executive.

Readers concerned about seasonal effects on tithing can learn how to “sustain generosity” during the weaker summer months. Technology like push notifications and text messages is encouraged as a way to remind people to tithe. There is also some emphasis on messaging, as pastors are told to “make sure your generosity-focused sermons are hitting home with your audience”.

Churches need money to stay active, and it’s natural that pastors would want to maintain a healthy cash flow. But the brazen language of Church Executive reminded me of the language of profit-maximizing firms. This got me thinking: What are the other ways in which religions act like a business?

This post is my attempt to understand religions as if they were businesses. This isn’t a perfect metaphor. Most religious leaders are motivated by genuine beliefs, and few are motivated primarily by profit. But it can still be instructive to view religions through the lens of business and economics, if only as an exercise. After working through this myself, I feel like I have a better understanding of why religions act the way they do.

Competition

As with any business, one of the most pressing concerns of a religion is competition. According to sociologist Carl Bankston, the set of religions can be described as a marketplace of competing firms that vie for customers. Religious consumers can leave one church to go to another. To hedge their bets on the afterlife, some consumers may even belong to several churches simultaneously, in a strategy that has been described as “portfolio diversification”.

One way that a religion can ward off competitors is to prohibit its members from following them. The Bible is insistent on this point, with 26 separate verses banning idolatry. Other religions have been able to eliminate competition entirely by forming state-sponsored monopolies.

Pricing

Just like a business, religions need to determine how to price their product. According to economists Laurence Iannaccone and Feler Bose, the optimal pricing strategy for a religion depends on whether it is proselytizing or non-proselytizing.

Non-proselytizing religions like Judaism and Hinduism earn much of their income from membership fees. While exceptions are often made for people who are too poor to pay, and while donations are still accepted, the explicit nature of the membership fees help these religions avoid having too many free riders.

Proselytizing religions like Christianity are different. Because of their strong emphasis on growth, they are willing to forgo explicit membership fees and instead rely more on donations that are up to the member’s discretion. Large donations from wealthy individuals can cross-subsidize the membership of those who make smaller donations. Even free riders who make no donations at all may be worthwhile, since they may attract more members in the future.

Surge Pricing

Like Uber, some religions raise the price during periods of peak demand. While attendance at Jewish synagogue for a regular Shabbat service is normally free, attendance during one of the High Holidays typically requires a payment for seating, in part to ensure space for everyone.

Surge pricing makes sense for non-proselytizing religions such as Judaism, but it does not make sense for proselytizing religions such as Christianity, which views the higher demand during peak season as an opportunity to convert newcomers and to reactivate lapsed members. Thus, Christian churches tend to expand seating and schedule extra services during Christmas and Easter, rather than charging fees.

Product Quality

Just as business consumers will pay higher prices for better products, consumers of polytheistic religions will pay higher “prices” for gods with more wide-ranging powers. Even today, some American megachurches have found success with the prosperity gospel, which emphasizes that God can make you wealthy.

Of course, not all religious consumers will prefer the cheap promises of the prosperity gospel. For many religions, product quality is defined primarily by community, a sense of meaning, and in some cases the promise of an afterlife.

Software Updates

A good business should be constantly updating its product to fix bugs and to respond to changes in consumer preference or government regulation. Some religions do the same thing, via the process of continuous revelation from their deity. Perhaps no church exemplifies this better than the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

For most of the history of the Mormon Church, individuals of African descent were prohibited from serving as priests. By the 1960s, as civil rights protests against the church received media attention, the policy became increasingly untenable. On June 1, 1978, Mormon leaders reported that God had instructed them to update the policy and allow black priests. This event was known as the 1978 Revelation on the Priesthood.

In the late 19th Century, when the Mormon Church was under intense pressure from the US Government regarding polygamy, the Church president claimed to receive a revelation from Jesus Christ asking him to prohibit it. This revelation, known as the 1890 Revelation, overturned the previous 1843 Revelation which allowed polygamy.

While frequent updates usually make sense in business, they don’t always make sense in religion. Most religions have a fairly static doctrine, as the prospect of future updates undermines the authority of current doctrine.

Growth and marketing

Instead of focusing only on immediate profitability, many businesses invest in user growth. As mentioned earlier, many religions are willing to cross-subsidize participation from new members, especially young members, with older members bearing most of the costs.

Christianity’s concept of a heaven and hell encouraged its members to convert their friends and family. In some ways, this is reminiscent of viral marketing.

International expansion

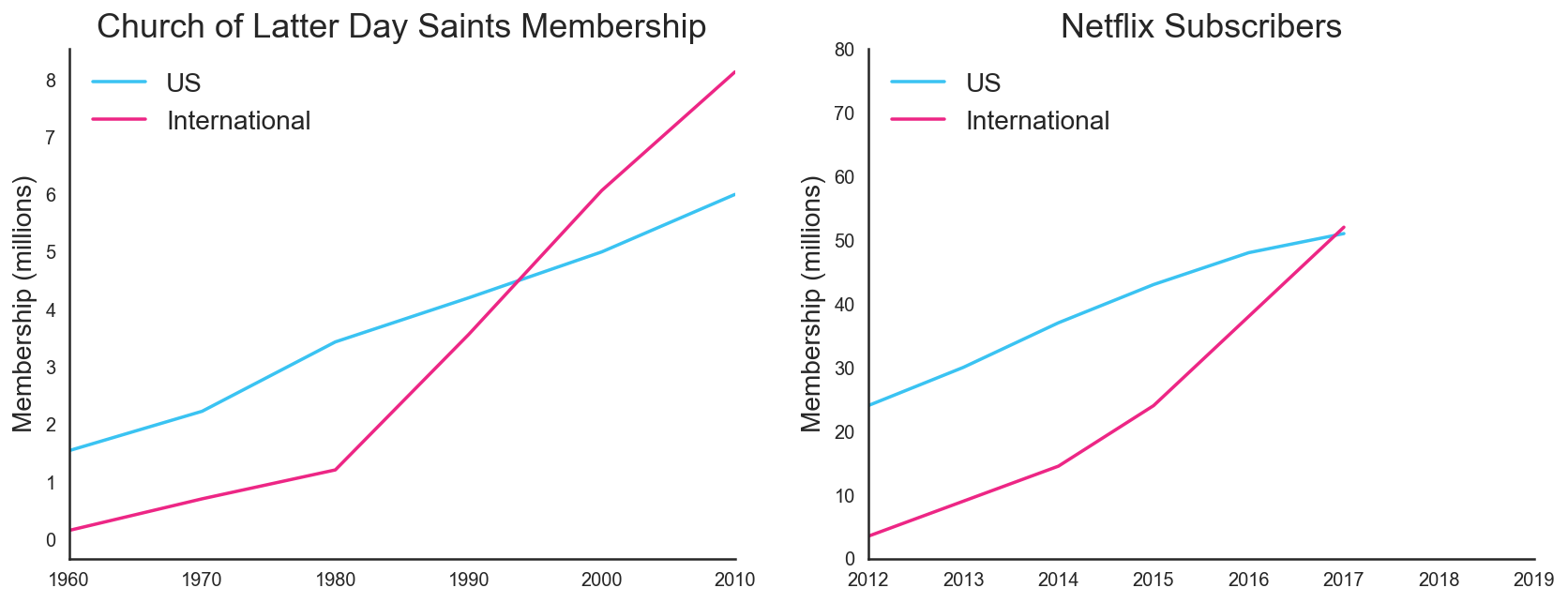

Facebook and Netflix both experienced rapid adoption, starting with a U.S. audience. But as U.S. growth began to slow down, both companies needed to look towards international expansion.

A similar thing happened with the Mormon church. By the 20th century, U.S. growth was driven only by increasing family sizes, so the church turned towards international expansion.

The graph below shows similar US and international growth curves for Netflix and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[1,2,3,4]

Branding

Like any company, most religions try to maintain a good brand. But unlike businesses, most religions do not have brand protection, and thus their brands can be co-opted by other religions. Marketing from Mormons and from Jehovah’s Witnesses tends to emphasize the good brand of Jesus Christ, even though most mainstream Christians regard these churches as heretical.

One of the most interesting risks to brands is genericide, in which a popular trademark becomes synonymous with the general class of product, thereby diluting its distinctive meaning. Famous examples of generic trademarks include Kleenex and Band-Aid. Amazingly, genericide can also happen to religious deities. The ancient Near East god El began as a distinct god with followers, but gradually became a generic name for “God” and eventually merged with the Hebrew god Yahweh.

Mergers and spin-offs

In business, companies can spin off other companies or merge with other companies. But with rare exceptions, religions only seem to have spin-offs. Why do religions hardly ever merge with other religions? My guess is that since there is no protection for religious intellectual property, religions can acquire the intellectual property of another religion without requiring a merger. Religions can simply copy each other’s ideas.

Another reason that religious mergers are rare is that religions are strongly tied to personal identity and tap into tribal thinking. When WhatsApp was acquired, its leadership was happy to adopt new identities as Facebook employees. But it is far less likely that members of, say, the Syriac Catholic Church would ever tolerate merging into the rival Syriac Maronite Church, even if it might provide them with economies of scale and more political power.

On Twitter, I asked why there are so few religious mergers and got lots of interesting responses. People pointed out that reconciliation of doctrine could undermine the authority of the leaders, and that there is little benefit from economies of scale. Others noted that religious mergers aren’t that rare. Hinduism and Judaism may have began as mergers of smaller religions, many Christian traditions involve mergers with religions they replaced, and that even today Hinduism continues to be a merging of various sects.

It’s worth repeating that economic explanations aren’t always great at describing the conscious motivations of religious individuals, who generally have sincere beliefs. Nevertheless, economic reasoning does a decent job of predicting the behavior of systems, and it’s been pretty interesting to learn how religion is no exception.