Three questions for social scientists: Internet virtue edition

19 Jun 2017This isn’t news to anybody, but the internet is changing our culture. Recently, I’ve been thinking about how it has changed our moral culture, and I realized that most of our beliefs on this topic are weirdly in tension with one another. Below are three questions that I feel are very much unresolved. I don’t have any good answers to them, and so I think they might be good topics for social science research.

1. Moral Substitution and Moral Licensing versus Moral Contagion

When people do the Ice Bucket Challenge or put a Pride symbol on their profile avatar, they are sometimes accused of virtue signalling, a derogatory term akin to moral grandstanding. Virtue signallers are said to care more about showcasing their virtue than about creating real change.

Virtue signalling is bad, allegedly, for two reasons: First, instead of performing truly impactful moral acts, virtue signallers spend more time performing easy and symbolic acts. This could be called moral substitution. Second, after doing something good, people often feel like they’ve earned enough virtue points that they can get away with doing something bad. This well-studied phenomenon is called moral licensing.

While there are some clear ways that virtue signalling can be bad, there is another way in which it is good. Doing good things makes other people more likely to do good things. This process, known as moral contagion, was famously demonstrated in the Milgram experiments. Participants in those experiments who saw other participants behave morally were dramatically more likely to behave morally as well.

If the social science research is right, then we can conclude that putting a Pride symbol on your avatar make you behave worse (via moral licensing and moral substitution), but it makes other people behave better (via moral contagion). This leaves a couple of open questions:

First, how do the pros and cons balance out? Perhaps your Pride avatar is net positive if you have a large audience on Facebook, but net negative if you have a small audience. And second, how does moral contagion work with symbolic acts? Does the Pride avatar just make other people add Pride symbols to their avatars? Or does it make them behave more ethically in real and impactful ways?

We are beginning to get some quantitative answers to these questions. Clever research from Linda Skitka and others has shown that committing a moral act makes you about 40% less likely to commit another moral act later in the day (moral licensing), whereas hearing about someone else’s moral act makes you about 25% more likely to commit a moral act later in the day (moral contagion), although the latter finding fell short of statistical significance. More research is needed though, particularly when it comes to social media and symbolic virtue signalling.

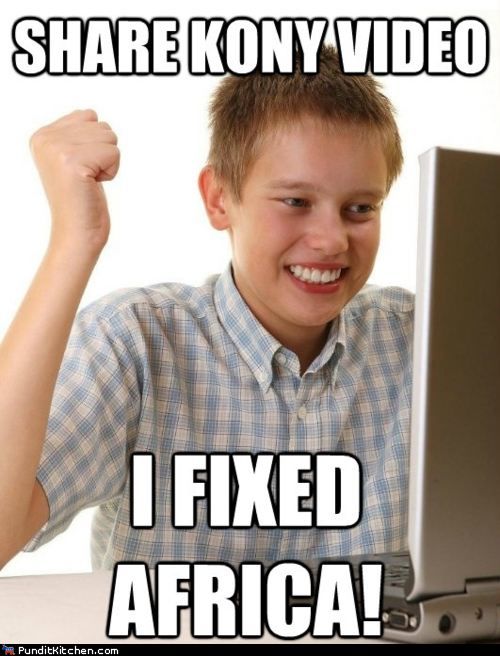

2. Slacktivism versus Violent Revolution

This question is more for political scientists.

Many people are concerned that the internet encourages slacktivism, a phenomenon closely related to moral substitution. It’s easier to slap a Pride symbol on your Facebook than to engage in real activism. In this way, the internet is really a tool of the already powerful.

On the other hand, some people are concerned that the internet cultivates violent radicalism. Online filter bubbles create anger and online networks create alliances, ultimately leading to violent rhetoric and homegrown terrorism. Many observers already sense the undercurrents of violent revolution.

How can we be worried that the internet is causing both slacktivism and violent radicalism? One possibility is that we only need to worry about slacktivism, and that the violent rhetoric isn’t actually violent – it’s just rhetoric. But the other possibility is that the internet has made slacktivists out of people who otherwise wouldn’t be doing anything at all, and it has made violent radicals out of people who would otherwise be mere activists. I’m not sure what the answer is, but it would be useful to understand this more.

3. Political Correctness: Overton Windows versus Wolf Crying

Perhaps because of filter bubbles on both sides of the political spectrum, the term “political correctness” is back with a vengeance. Leaving aside the question of whether political correctness is good or bad, it would be interesting to understand whether it is effective. On the one hand, political correctness may help define an Overton Window, setting useful bounds around opinions that can be aired in polite company. But on the other hand, if the enforcers squeeze the boundaries too much, imposing stricter and stricter controls on the range of acceptable discourse, they risk undermining their own credibility by “crying wolf”. For what it’s worth, many internet trolls credit their success to a perception that social justice activists overplayed their cards. I’m not sure how much to believe them, but it seems possible.

Just in terms of effectiveness, is there a point at which political correctness starts to backfire? And more broadly, what is the optimal level of political correctness for a society? Neither of these questions seems easy to answer, but I would love to learn more.