How failed replications change our effect size estimates

10 Jul 2014Yesterday I posted a very unscientific survey asking researchers to describe how failed replications changed their subjective estimates of effect sizes. The main survey asked for “ballpark estimates” of effect sizes, but an alternative interactive version allowed researchers to also report their uncertainty by specifying both the mean and variance of their posterior distributions. Thanks to everyone who participated. I won’t be analyzing any new data after this, but it’s never too late to publicly share your estimates!

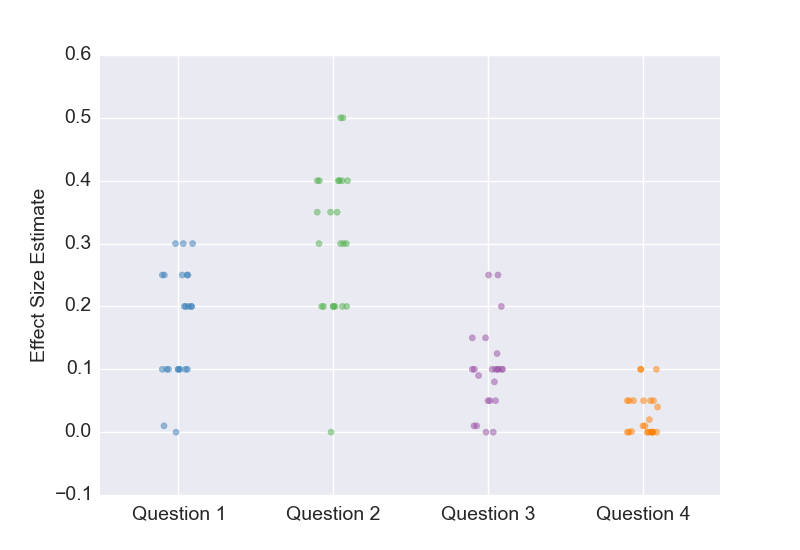

Here are the questions.

Question 1. A 2009 experiment with 50 subjects (25 per cell) is published in Psych Science. The experiment does not require any special equipment other than a questionnaire. It is not pre-registered. The results show an effect size of d=0.5. Let’s define the true effect size to be the average effect size of an infinite number of replications that the original experimenter would deem “reasonably exact” in advance. Based on this information alone, what is your ballpark subjective estimate of the true effect size?

Question 2. What if the experiment had been pre-registered?

Question 3. Assume again that the experiment was not pre-registered. Now imagine that a pre-registered replication attempt with the same sample size estimated the effect size to be d=0.0. At the time of pre-registration, the original experimenter deemed it “reasonably exact”. Based on this replication and the original experiment, what is your ballpark subjective estimate of the true effect size?

Question 4. What if the replication attempt had 300 subjects per cell?

Here are the results.

Keeping in mind all the caveats about sampling bias and other issues, here are a few observations:

-

The original study reported an effect size of d=0.5, but the results for Question 1 tell us that most researchers believed the true effect size was closer to d=0.2, which is roughly in line with my own estimate. Had I allowed researchers to state their uncertainty, I suspect that many would find it quite possible that even the sign of the effect was wrong. This isn’t really surprising to me, but I think we should take a moment to reflect on what this means. When a scientist reports a result, most other researchers believe it is massively overstated. I know that there are still some researchers who want little or no changes to the status quo, but I’d like to live in a world where people actually believe the claims that scientists make. That’s why I’m a strong supporter of all the attempts to fundamentally change how scientists do research.

-

If you want people to have more confidence in your findings, pre-registration can make a big difference.

-

While it’s not apparent from the plot, almost all respondents reduced their effect size estimate upon hearing about failed replications (Question 3 and 4 compared to Question 1).

-

As some have pointed out, the original experiment falls a bit short of statistical significance. This was an oversight, as I forgot to check the p-value after changing some of the values. I don’t think this is a huge deal, since posterior estimates shouldn’t really depend too much on whether the results cross an arbitrary threshold. But apologies for the error.

-

My estimates were .25, .40, .10, .05.

-

I wish I included another question asking what people would have thought of the original study if it was conducted in 2014.